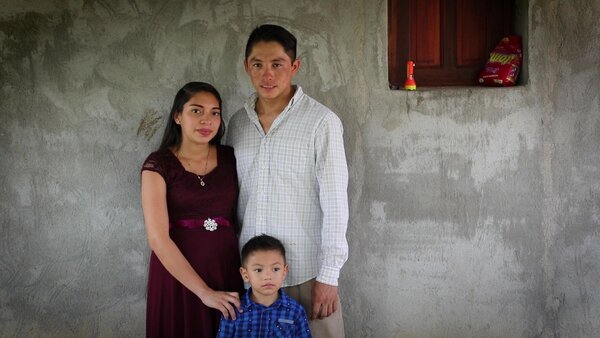

‘I came home to El Salvador to work my land again and try to get my life back’

I met Salvadoran farmer José Cirilo Mendoza during a recent mission to document the effects of five consecutive years of drought in Central America's so-called ‘Dry Corridor' — a disaster in slow motion affecting the lives of over 2 million people across Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua, as well as El Salvador. Pushed to the brink, José Cirilo — who learned farming from his father — embarked on a perilous journey to the United States, but was caught at the border and sent back. The World Food Programme (WFP) is helping him and other farmers in the region stay on their lands by promoting activities like community gardens, soil conservation, watersheds and water harvesting, as well as providing emergency food assistance and training.

Here is José Cirilo's story of hardship and migration, and of lingering hope that these resilience-building activities can help revitalize the land and change his life and those of his wife — now pregnant with their second child — and 4-year-old son.

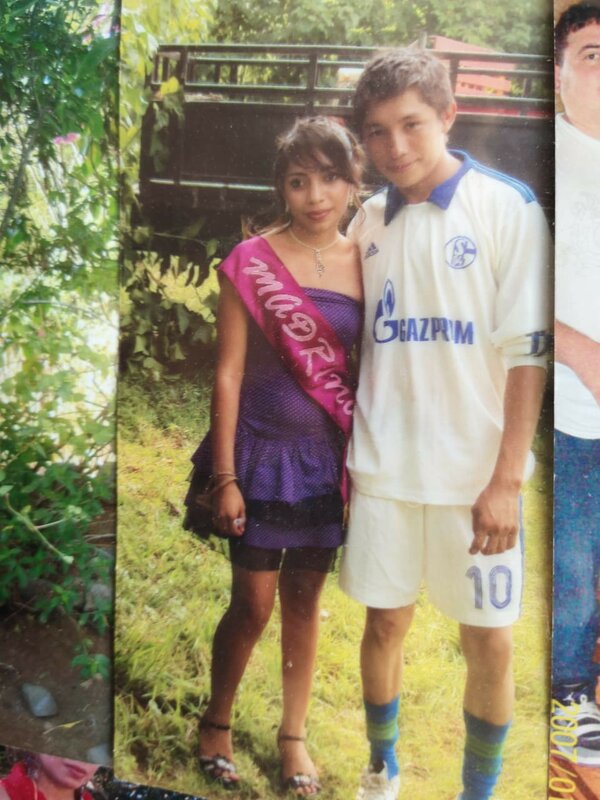

"My wife and I got married when I was 21 and I started planting my farm.

We both wanted to have children but because of the drought we couldn't cultivate enough. The land wasn't yielding enough. It doesn't rain anymore, the temperature gets warmer, the field dries up and then we can't cultivate — everything dries up. Nowadays we harvest half as much as we used to, if not less. Sometimes we lose our crops and have to buy the food we need for the year.

This is why I decided to leave: I needed to work, lift myself up, be somebody and do something.

I had a few savings and invested them in trying to get to the United States. It took me about three months to reach the US border. I stayed two days in Guatemala. After that, I travelled by bus — day and night. Sometimes I wouldn't even sleep. I hid about 20 days in a mountain, and then I was told to cross the river into US territory. We ran but got caught. We were detained for a while and then I was sent back to El Salvador.

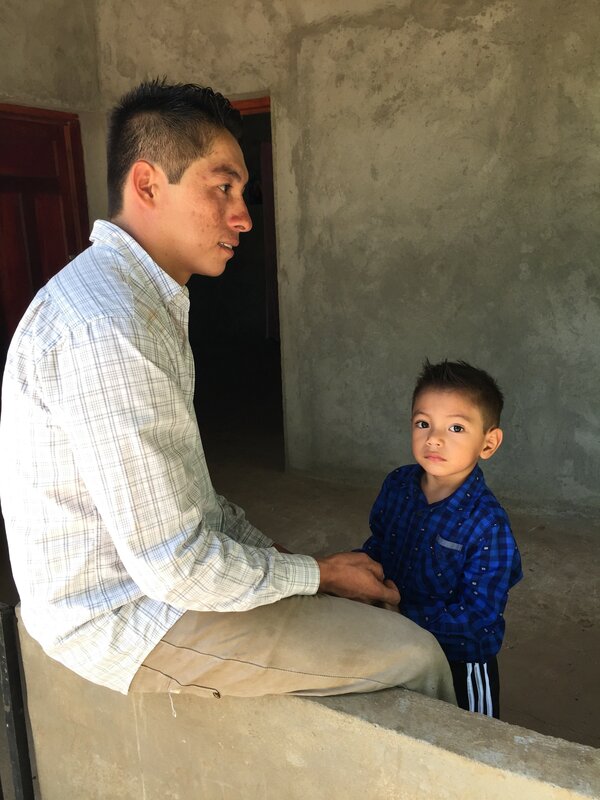

So I came back here to work my land again. I came back to start over as a farmer and try to get my life back here in El Salvador.

It's hard having a family and not knowing how to prosper, how to feed them. Wanting to see them grow healthy, and not having the necessary resources.

Sometimes I take odd jobs so I can buy what we need at home. WFP's project has helped us a lot financially — now I can buy corn, which is what we need the most.

If things go back to what they were before the drought, I will stay here in El Salvador. Otherwise, I think I will leave again because there is no work here. One can't survive."

- - -

José Cirilo participated in a WFP project in which members of his native San Andrés community received cash transfers as they set up their own community orchard, where they can grow fresh vegetables such as tomatoes, green peppers, eggplants and radish.