Inside WFP’s Cyclone Idai Response: Helicopters, Hope and Humanitarian Heroes in Mozambique

Two weeks after Cyclone Idai bashed through Mozambique, I travel to Beira.

As I fly in at night, spots of lights scatter the ground, like the glare of cat eyes in the bush. The city should be lit up — this is after all Mozambique's second most populated urban area. But Cyclone Idai plunged Beira into darkness — and an eerie silence — on the night of 14 March, after it ripped apart and shredded everything in its path — families, homes, livestock and businesses — before dying a sudden death in the mountains of Zimbabwe.

At Beira airport, military and humanitarian aircrafts litter the tarmac. On board, all passengers are dressed in humanitarian organizations' clothing, with heavy duty boots, tents and sleeping mats attached to their backpacks. They're the so-called ‘responders' — who else would travel to the previously bustling port city at this time?

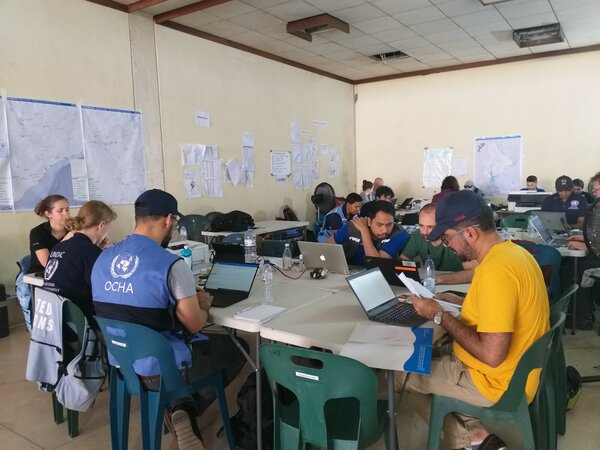

The humanitarian operations centre is at the airport, leading out to tarmac. The energy level as hundreds of responders push, shout, run is overwhelming — and not for the faint-hearted as the stench of sweat, rot and mold persists.

It is late, the rest of the world have already enjoyed their dinner, put their children to bed, and are tucking in for the night, possibly watching a bit of telly, maybe — just maybe — wondering what they can do to help the desperate people of Mozambique. The responders too have eaten: crisps, nuts, energy bars — everybody shares what they have. A hot shower and a bed have been, and still are, unavailable to most. Who has time anyway — each one of them is playing a critical role in saving lives.

As the waters recede, there is still much to do. The inland sea has morphed into acres of mud. Every Mozambican in the path of the cyclone requires humanitarian assistance — 1.7 million of them.

On the WhatsApp group created by national and international NGOs, UN agencies and the Red Cross, conversations are incessant: "Any spare batteries?", "Torches anyone?", "Anyone know of accommodation?" The humanitarian response teams works in close coordination with the INGC, the national disaster management agency, which guides, oversees and leads the action on the ground.

The noise level increases as I hop onto a food-laden United Nations Humanitarian Air Service (UNHAS) helicopter heading for Munamicua, a community in southern Buzi province. On board this MI-8, I wear ear muffs. They are not complimentary though: our pilots openly count them when we disembark.

In the village, I meet 14-year-old Maria Pedro Manuel. She has walked six kilometers with her sister to the food distribution area. As she waits with more than 2,000 other weak and frightened people, she tells me: "I have no favourite food, we eat to survive." Maria, her sister, young nieces, nephews and grandfather were abandoned to the elements when the cyclone ripped down their tiny home. "We had nowhere to go, nowhere to hide, we held onto each other. My uncle died and I lost my identification document and my school books," she adds.

"If it were not for the big helicopters bringing food, I don't know what would become of us. We have lost all our seeds too." The sadness is engraved on Maria's face, I fear it will never leave her. The cyclone has stolen her youth as she tells me her worry is for the children as they have no clothes, shoes, food or water. "We were small farmers, but I do not want to be a farmer, I want to leave."

I say what anyone else would say. I tell her I am sorry for her loss and hope that she does get to fulfill her aspirations. But I also tell her, as a WFP staff member knows with certainty, that the world knows what has happened to her community and we know how to get to them; that we will not stop delivering humanitarian assistance and, long after all the visitors and media will have left, we will stay on and support the recovery effort with the help of our donors and partners on the ground. For the first time in over an hour, Maria smiles. It is a moment of silence — and a most welcome one.

Loud noises interrupt the moment. "Move, move, move," says the voice of Cesar Arroyo, WFP's Emergency Coordinator, who is organizing with great authority the offloading of 10 metric tons of food from three UNHAS helicopters. Once the food is offloaded, WFP has to distribute it to the people waiting for their three-day food basket of rice, beans and oil. It is not an easy task. The people are organized into twelve pocket areas; local helpers are assisting with the offloading, registering names and dividing the food under a 40-degree sun. I get back to work, moving boxes of oil from one end to another.

Cesar, a field veteran, joined WFP in 1997 and has spent his career reaching the most vulnerable people in critical contexts such as Angola, Darfur and the Ebola response in west Africa. We are all musicians in his orchestra: we watch his arms and body language closely and within six hours the offload and distribution is completed.

Whether at the operations centre, on a helicopter or in the community, the loud ringing of aircraft engines and voices in your ears is beautiful. It means people are been saved, lives will change and communities will recover.