COP28: 4 ways the world can curb loss and damage as climate change fuels hunger

When world leaders meet in Dubai for COP28 – the UN Climate Change conference held from 30 November until 12 December – loss and damage connected to climate change will be high on the agenda.

2023 is expected to be the hottest on record, experts believe, bringing with it disastrous consequences.

Tackling the climate crisis starts by averting the problem in the first place, chiefly by reducing global emissions. But simultaneously we need to equip communities with the tools they need to deal with losses and damage to homes, crops, livelihoods and infrastructure such as roads and bridges.

ShareTheMeal: WFP app reaches 200 million meals milestone

We can strengthen the hand of people seeking to protect the ecosystems their lives depend on and their cultural heritage.

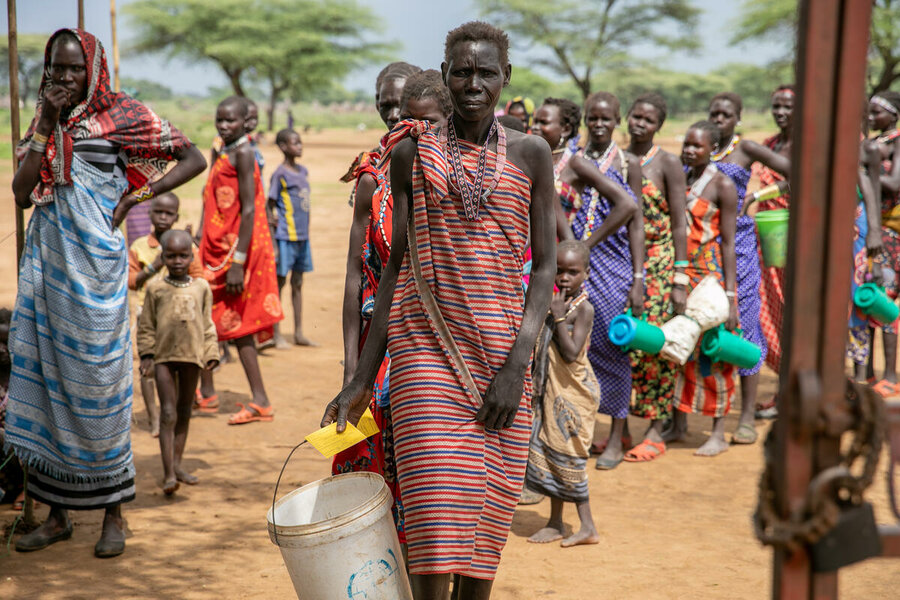

Time and time again we see that people suffering the worst loss and damage linked to climate change are those who did the least to cause the problem.

People in poor and low-income countries, as ever, bear the brunt – the World Food Programme supports over 15 million people a year in such countries to protect themselves from climate impacts.

African countries contribute only 4 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, yet experience some of the most devastating impacts of droughts and floods: crops wither, people lose their livestock and preventable tragedies occur.

Countries such as Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia in the Horn of Africa have suffered three years of extreme drought caused by climate change, pushing 23 million people into severe hunger. In Somalia, when the rains did finally arrive in March this year, instead of providing relief to farmers they triggered flash floods, displacing 140,000 people across the country.

Acting before disaster strikes

WFP works with communities to build their resilience to withstand climate shocks, including through early-warning systems linked to anticipatory actions – acting ahead of time to reduce the severity of the impact.

Ahead of predicted worsening drought at the end of 2023, WFP activated a region-wide anticipatory-action response to protect people from failed harvests and disrupted markets in Lesotho, Madagascar, Mozambique and Zimbabwe – providing cash to 555,000 people that enables them to protect their livestock and prepare for water shortages.

Shupikai is one farmer in Zimbabwe who received text messages through the anticipatory action programme. “They tell me whether it’s going to rain,” he told WFP. “With that, I know when to put fertilizer in my fields.”

Protecting livelihoods with insurance

WFP also works with local governments and communities to help them access insurance protection for their crops and livestock so that in the event of a climate hazard community members receive a cash payout for the losses.

This enables people to protect their livelihoods by supplementing lost incomes or buying food or additional crops. Such payouts go some way to compensate farmers for the loss of crops such as maize and beans, helping them avoid damaging coping strategies such as taking their children out of school, or selling their livestock.

After receiving a payout of US$53, Khadija, a farmer from Malawi, told WFP: “I’m very grateful for this immediate relief but I am also hopeful that with the different farming techniques I am learning through the project, I will not be vulnerable to climate shocks over time”.

Nature as the solution

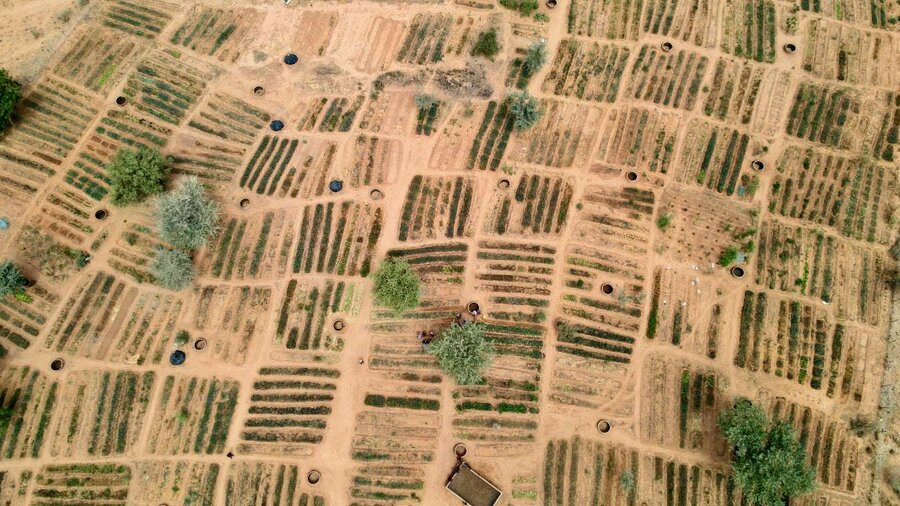

Physical protection is another way to minimize loss and damage. Hillsides can be terraced to avert landslides; hedgerows can counter soil erosion while communal ponds can increase water supplies in times of drought. Such ecosystem-based approaches are proven successes.

In Niger, WFP worked with communities on an integrated resilience programme – combining land rehabilitation, efforts to get children back to school and improve access to food and nutritional support. Following a particularly poor rainy season in 2021, 80 percent of participating villages did not require humanitarian assistance – illustrating their ability to withstand climate shocks now.

Emergency response

The final layer of protection is emergency response. When communities with insufficient preparedness and adaptation suffer loss and damage, humanitarians can step in to provide crucial support in the form of food, cash, temporary shelter or healthcare, among other things.

This was the case during the devastating floods last year in Pakistan which submerged one third of the country. WFP worked with the Government to provide emergency food, cash and nutrition assistance to affected people, as well as logistical support to Pakistan’s National Disaster Management Authority and humanitarian organizations.

With climate-related disasters continuing to worsen and compound with other shocks including conflict and economic downturns, the humanitarian system is at its breaking point.

The gap between needs and available funding is widening and communities around the world are suffering. We need urgent and ambitious political action to avert, minimize and address loss and damage in communities that are particularly vulnerable to negative climate impacts.

Put simply, if the world does not step up, millions of people will be at the mercy of treacherous extreme weather events.