How Anticipatory Action helps people prepare as extreme weather strikes

When a disaster strikes, every hour counts – helping communities to prepare ahead of the next extreme-weather shock is critical.

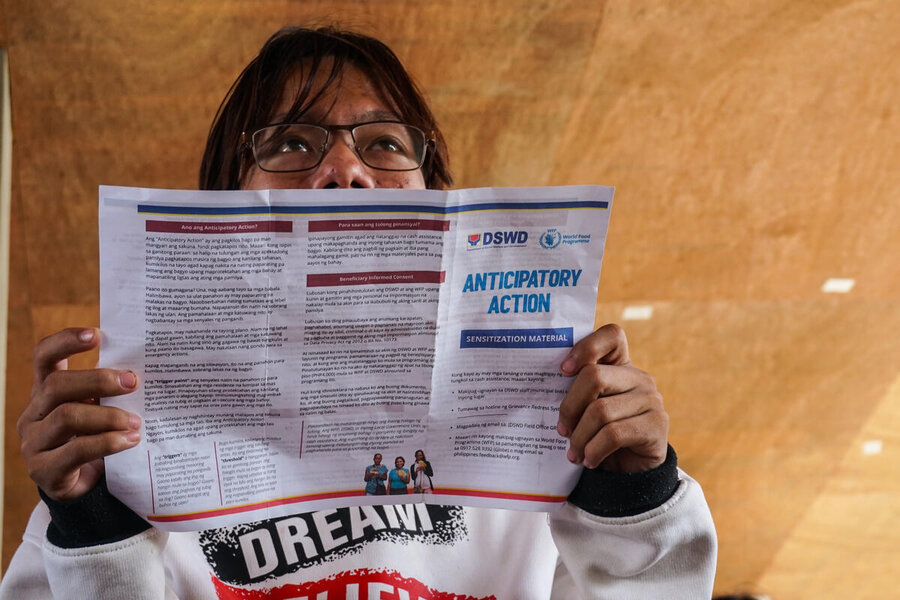

Cyclone Fung-wong, which made landfall in the Philippines on Sunday (9 November) provided a stark reminder of why the World Food Programme invests in Anticipatory Action (AA). By acting ahead, WFP has been able to distribute emergency cash assistance to 42,000 families – around 210,000 people.

Hurricane Melissa, which devastated Jamaica in October, wreaking havoc in Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, highlights how activation thresholds, or triggers, help decide when to act.

In Haiti, for instance, a trigger threshold prompted the Government, supported by WFP and its UN and NGO partners, to issue early-warning messages to 3.5 million people and transfer cash assistance to nearly 50,000 people.

In Cuba, when early warning data reached the readiness trigger (standby alert) and approached the action trigger (the point when anticipatory measures begin) WFP moved fast, launching a logistical operation within 48 hours, transporting 280 metric tons of prepositioned food (rice, grains and oil) to the eastern region – reaching close to 182,000 people.

Shirin Merola leads WFP’s global Country Support Team for Anticipatory Action. In the Q&A below she explains how a bold idea hatched in 2015 has turned into a global programme reaching millions ten years on.

Tell us about Anticipatory Action at WFP

Shirin Merola: WFP started exploring the Anticipatory Action (AA) approach in 2015. A few donors came on board early, and some partner countries invited us to test the approach. That’s when we began building the systems.

In the early days, it was mostly about laying the groundwork – understanding how AA differs from traditional emergency preparedness, and figuring out how all the pieces fit together.

Then came 2019 – a turning point. WFP activated Anticipatory Actions in Bangladesh ahead of major floods. It was our first large-scale rollout, and the first-ever cash transfer based on a disaster forecast.

People received cash support days before the floods hit. That helped them prepare, but it also saved time and money for humanitarian agencies and donors. Instead of responding 100 days after a flood, we were acting 48 hours before – at half the cost.

We’ve since expanded from five countries to more than 44, carrying out over 30 activations; over 6.2 million people are now eligible for anticipatory assistance.

Describe the process

SM: We act when forecasts give enough lead time to implement anticipatory actions before the impacts of a predicted hazard fully unfold. This involves working closely with national weather services to improve the accuracy and timing of forecasts.

We also help governments define ‘triggers’ – in short, the level of predicted impact that signals it’s time to act.

Is it one-size-fits-all?

SM: No – each country and context has its own plans and triggers. WFP partners with meteorological agencies and universities to improve forecasting, train local teams and adapt models to local conditions.

We also work with disaster management agencies to design Anticipatory Action plans that kick in before a flood, cyclone or drought.

Is AI playing a role, too?

SM: Yes. In Eastern Africa, for example, WFP is using AI to turn low-resolution satellite images into high-resolution ones – making rainfall forecasts more accurate and more accessible.

Who benefits?

SM: We focus on communities most at risk. Take Somalia, for example. In 2024, WFP and the Government of Somalia activated an Anticipatory Action plan for floods across four districts. The activation reached almost 80,000 people across multiple activations, with cash assistance provided up to eight days before floods arrived.

And weeks before Cyclone Remal struck on 26 May 2024, the Government of Bangladesh and WFP took action to help people in coastal areas protect their homes and their livelihoods. Two months later, similar steps were taken in five flood-prone districts in the Jamuna Basin.

Altogether, more than 630,000 at-risk people received cash assistance to reinforce homes, evacuate safely and purchase essential items such as food and medicine. The activation in the Jamuna basin stands as the largest AA activation globally to date, and the activation ahead of Cyclone Remal marks the first time AA has been triggered before a cyclone in Bangladesh.

Would you say AA is more effective than traditional post-shock response?

SM: Yes – evidence tells us that providing support ahead of climate hazards avoids food security disruptions, strengthens outcomes and contributes to better psychological well-being for those affected.

What sort of support does WFP provide?

SM: It depends on the context. In Southern Africa, ahead of the 2023–24 El Niño season, WFP reached 230,000 people with cash and agricultural inputs, and 1.2 million with early warning messages – six to 12 months before the response kicked in.

That early support helped people avoid harmful coping strategies – like selling assets or pulling children out of school. It also helped protect food security.

In countries with strong social protection systems, we help governments use those systems to quickly distribute assistance – whether that’s cash or other support.

We also work at the policy level. In countries like the Philippines, Mozambique and Indonesia, we support governments to revise contingency plans, update laws and protocols, and ensure domestic financing can be allocated for anticipatory action.

Mozambique is an outstanding example of AA in action. The Government has integrated anticipatory action into its national disaster management plans – for cyclones, floods and droughts.

It starts with planning.

SM: Yes, that’s the longest and most detailed part.

We define triggers, decide who monitors them, who gets what, when, and how much funding is needed. This involves coordination across multiple teams – programmes, logistics, finance and more.

Once plans are approved and funding is secured, we monitor forecasts with governments. When a trigger threshold is met, we send out an activation notice. That unlocks pre-arranged funds and kicks off the implementation of anticipatory actions response.

Coordination is essential. At the country level, technical working groups bring partners together to align on triggers, anticipatory actions and funding.

Regionally, we’re seeing more collaboration through joint task forces between UN agencies and civil society.

Globally, we work through platforms like the Anticipatory Action Task Force, the Anticipation Hub and the Risk-Informed Early Action Partnership. These enable practitioners to share knowledge, strengthen advocacy and push for collective progress.

All of this depends on sustainable funding, of course.

SM: For anticipatory action to work, funding needs to be available before a crisis hits – and accessible the moment a trigger is activated.

Governments are increasingly investing their own resources. Donors are also contributing to pooled funds like the UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) and WFP’s own trust fund, managed by the Climate and Resilience Service.

In a tight funding environment, anticipatory action is proving to be a smart investment – especially in fragile contexts. It’s faster, cheaper and more effective than traditional humanitarian response.

Donors are taking note. They’ve pledged to scale up long-term funding and improve coordination around anticipatory action – and they must come through.