In Guinea Bissau, students with disabilities hit the books to make their parents proud

With a smile on her face, Adama Baldé greets the bell that marks the morning meal.

Using a cane, the 14-year-old visually impaired girl makes her way to the school canteen behind the Bengala Branca school in Guinea Bissau’s capital, where dishes of steaming rice and sauce are being served.

"This meal gives me strength and improves my concentration in class,” says Adama as she sits on a concrete bench savouring her meal.

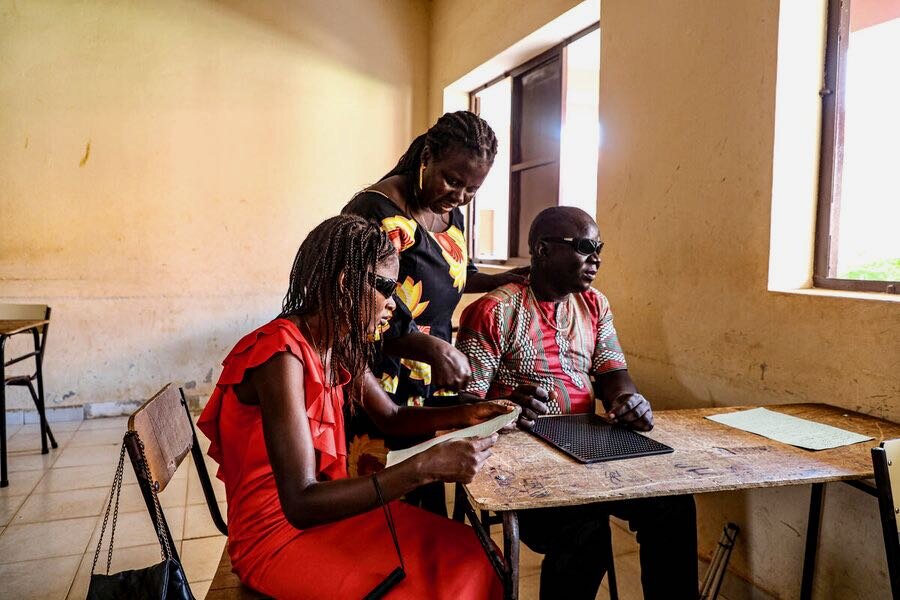

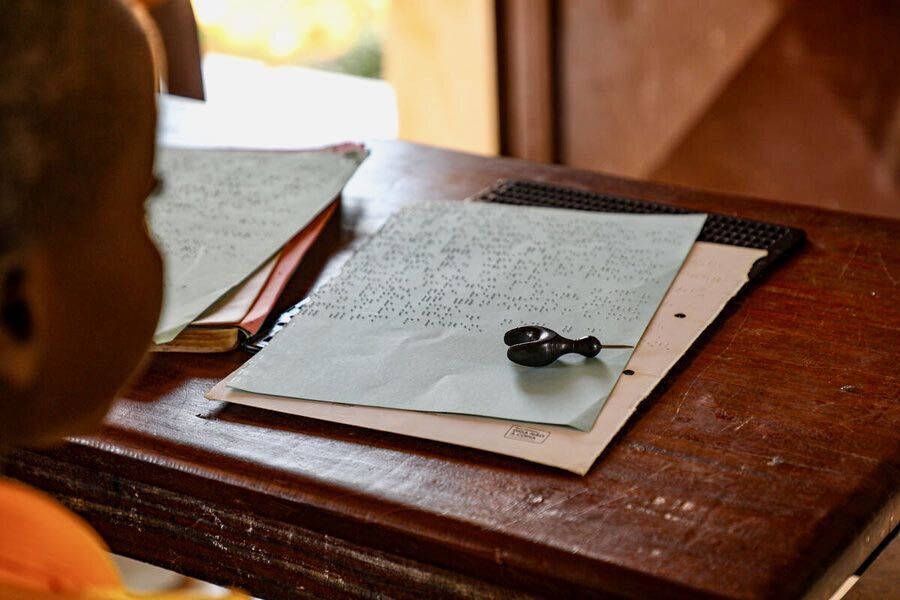

Translated as “white cane” in Portuguese, the West African country’s official language, Bengala Branca is the country’s first inclusive school, bringing together children with and without disabilities.

The boarding school is part of a broader initiative rolled out by the World Food Programme (WFP), Guinea Bissau’s government and international nongovernmental group, Humanity & Inclusion, to give children with disabilities greater access to the public school system - along with a nourishing WFP school meal.

In the process, the project Education Without Borders, aims to help tackle deep-seated prejudice and unequal treatment of children with disabilities in Guinea Bissau and elsewhere in the region, which often hamper their chances of becoming healthy and successful adults.

“Because you are born with a disability, you are not put in school, you are not taken to the hospital,” says Lázaro Barbosa, president of the Federation of Associations for the Defense and Promotion of People with Disabilities in Guinea-Bissau, which collaborates with WFP in better identifying and integrating children with disabilities in schools.

In some cases, Barbosa and others say, parents think having a child with a disability is a curse, or tied to witchcraft, and try to hide them away. Others are abandoned.

"My parents thought I was a devil and didn't want to be made fun of by the villagers," says one sixth grader in the programme, whose identity is being withheld for their protection. "But now I hope to make them proud of me, because I'm going to become a French teacher soon.”

School for all ages

Guinea Bissau is not the only country where WFP works with partners to draw people with disabilities of all ages to school, partly thanks to nourishing meals. In Venezuela, for example, WFP’s school meals programme rolled out last year now reaches more than 15,000 children, adolescents and adults, and their families, in 300 schools across eight states.

Among them: 52-year-old Luis Enrique, who has a cognitive disability and is now going to school for the first time.

"Some people say it's too late, but I don't think so,” says his father and carer, Luis Garcia, 72. “Now I know he can do well when I am no longer around.”

In Guinea-Bissau, an estimated 16 percent of children aged between 5 and 17 live with some form of disability. Their access to health, education, social assistance and other services is extremely limited.

A World Bank survey of these and other barriers facing people with disabilities in 10 sub-Saharan African countries concludes this makes high-quality education for children all the more vital.

“We do not want to leave any child out of the education system and without a healthy nutrition,” says WFP Representative and Country Director in Guinea Bissau, Claude Kakule. "We believe children with disabilities have potential, they just need the right support."

Launched in 2020, the Education Without Borders project now reaches all 852 schools in Guinea Bissau covered by WFP's school meals programme. We and our partners are now trying to map children with disabilities across the country to better identify and assist them, and are looking at other ways to better support inclusive education.

WFP also collaborated with partners and Guinea Bissau’s Ministry of Education to create a special government directorate for inclusive education, with staff learning first-hand from a similar effort in Burkina Faso.

"This immersion enabled us to become aware of the need to set up a specific schooling programme for people with disabilities in the country,” says Manuel Malam Jafono, head of the new Directorate General for Inclusive Education.

Under the leadership of Barbosa’s federation, WFP also participates in efforts to build the capacity of civil society groups and others advocating for the rights of children with disabilities to education and other fundamental entitlements.

"These children have the right to an education so that they can contribute to the country's development,” Barbosa says, adding the group plans to launch an awareness campaign to get more parents to send children with disabilities to school.

Food assistance central

For youngsters and their parents, WFP’s food assistance is central to this goal. It includes take-home rations for learners with disabilities, which provide a buffer against hunger, and initially cash assistance to especially vulnerable families.

"If this programme were to come to an end one day, it would be yet another abandonment for these children, who have already been damaged by life,” says Aissatou Djalo, a blind teaching assistant for pupils who are visually impaired at Bengala Branca school. Djalo herself graduated from the school, going on to earn a university degree.

At Mariposa - another school in the capital Bissau, which offers targeted education for hearing and speech-impaired learners - WFP is training young students to set up a school garden. Their fruit and vegetable harvests add nutritional diversity to school meals - and support broader government efforts to introduce health and nutrition programmes to schools.

"I used to lose pupils because they dropped out of school to go to work to feed themselves," says Mariposa headmaster Amaré Soares. "But now, with the help of this programme, in addition to the technical training they receive at school, the pupils know how to create and maintain a garden for their own meals.”