Conflict and funding cuts fuel soaring hunger in South Sudan

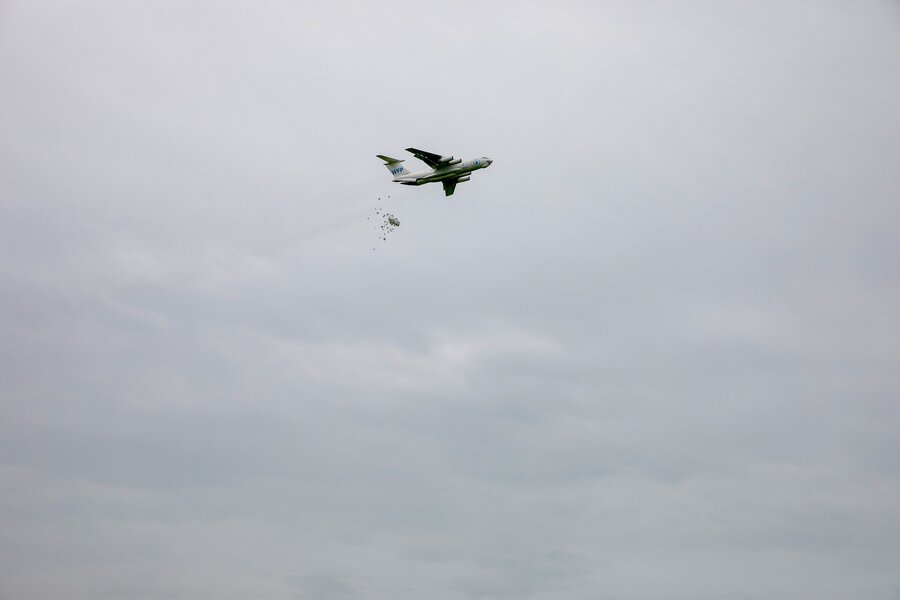

The white bags falling from the sky offered hope for Nyaduoth and her four children - casualties of months-long fighting ripping apart South Sudan’s Upper Nile State.

Uprooted by the conflict, their home burnt to the ground, the 50-year-old mother and her family sleep under the stars, sometimes soaked by heavy floods that wash away their crops - and so bereft they have no shoes. They have survived by eating leaves, wild grasses, and the occasional fish caught from a nearby river - until assistance from the World Food Programme (WFP) was recently airdropped in.

“Without assistance we can simply die,” says Nyaduoth of the rations of cereal, pulses, oil and salt. (As a conflict-displaced person, her last name is not being used). “If the food is not provided, then we don’t know where we should go.”

But those provisions are shrinking - and despite some improvements in parts of South Sudan, the overall hunger landscape risks darkening in the coming months. New expert findings project more than half the country’s population, or about 7.56 million people, could face crisis or worse food insecurity during next year’s April-July lean season, between harvests. More than two million children are expected to suffer from acute malnutrition.

In some of the most conflict-torn areas, some 28,000 people could experience catastrophic food insecurity, or IPC 5, the highest hunger level set by the Integrated Food Security Classification, or IPC. Most alarmingly, the IPC predicts parts of Luakpiny/Nasir County, where Nyaduoth lives, could tip into full-blown famine.

“This is an alarming trajectory,” says Mary-Ellen McGroarty, WFP’s Country Director in South Sudan. “The persistent high levels of hunger are deeply troubling.”

Shrinking budgets

The humanitarian crisis risks deepening for another reason. With aid agencies facing steep funding cuts, not enough assistance is reaching people who desperately need it. The cuts have forced WFP to reduce the target number of people we assist to just 3.7 million of the hungriest - and, even then, to slice food rations in some areas by up to half.

“We’re working with a shrinking humanitarian budget across the board,” says Ross Smith, WFP’s Director of Emergency Preparedness and Response. In a country with fragile functioning markets and where social services have limited reach, he adds, the cuts are devastating. “The humanitarian footprint has been really important for many vulnerable people across the country.”

The power of humanitarian assistance is seen in areas of relative peace and access - where the IPC found food security had slightly improved. “People have taken the first steps towards recovery,” says WFP’s McGroarty. “While this progress is encouraging, it is crucial that we sustain the momentum to ensure lasting positive change across all affected communities. Security and peace are fundamental prerequisites for achieving food and nutrition security."

WFP and other humanitarians are also making a difference for people fleeing another conflict: the one raging in neighbouring Sudan. At Renk border crossing, in northern South Sudan, we are providing fortified biscuits, cash and nutritional support to refugees and returning South Sudanese who arrive hungry and malnourished - assistance that is dwindling as funds dry up.

“When they find their way here, they are in a very dire state,” says Rose Ejeru, head of WFP’s Renk field office, of the new arrivals. “Many of them are already malnourished, many of them are already sick. So when they arrive here, their situation is very bad.”

Hard times

The fallout of the cuts is especially seen in the hungriest parts of the country, where WFP’s support is literally saving lives. Here, too, we have been forced to reduce food rations by more than one-quarter.

That includes emergency assistance airdropped into remote counties of Upper Nile state - an expensive, but last-ditch option for tens of thousands of families. We have also helicoptered in nutritional assistance on behalf of our humanitarian partners.

“We really appreciated WFP for providing this food,” says 73-year-old David, of the bags dropped near his village of Ngueny. “It is helping us a lot.”

Like Nyaduoth’s family, the father of eight and his children are homeless, their farm and slender food reserves destroyed by fighting. Heavy flooding and insect outbreaks - both fallouts of extreme weather - have wiped out his crops and sickened his livestock.

“Life is very hard right now,” David says, sitting on a grassy plain with a few trees dotting the skyline. “Everyone is fleeing, looking for a place where they can live temporarily. Even now, we don’t have shelters at all. We are just under these trees.”

Nyaduoth is also hostage to South Sudan’s erratic weather. Her family also has no shelter - not even a strip of plastic sheeting to protect them from the rains.

While the humanitarian support offers some relief, she is dreaming of better times. “Let peace prevail,” she says. “And let children have the hope of getting a good education.”

The World Food Programme (WFP) is providing life-saving assistance in South Sudan thanks to support from Canada, Denmark, the European Commission (ECHO), France, Germany, Ireland, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), the United Nations’ Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF), the United States and private donors.