Does AI hold the key to ending hunger?

Can AI end hunger?

Achieving zero hunger is a huge task and humanitarians need to use every advantage that is available to them. AI can be an incredibly important tool for tackling hunger smarter and faster – but it can’t end hunger on its own. However, by combining the best technology with the best academic research, and investing money behind it, AI – with a strong human element supporting – can play a massive role in creating a hunger-free world.

How is AI used in the humanitarian sector?

AI is used in a variety of ways in humanitarian work. It can save humanitarians time and money, meaning that every dollar spent has that extra reach and ability to make more of an impact. In emergencies, it cuts down damage assessment from weeks to hours, meaning responders can reach those in need much sooner. AI-led monitoring can see things that the human eye cannot, and support, or even lead on, search-and-rescue missions.

AI models can process vast amounts of data, improving targeting and detecting duplications in distribution lists, so that assistance goes to those who need it the most. When applied to supply chain, AI can help identify more efficient ways of sourcing and routing food assistance. In places where lives and livelihoods are put at risk by extreme weather, a combination of drone technology and AI modelling can provide guidance on what crops to grow, based on soil analysis and other factors, including early detection of infestation. Also, AI can be used to perform menial, time-consuming tasks, freeing humans to think creatively and focus on areas where they can have more meaningful impact.

Examples of AI successfully addressing challenges in humanitarian crises

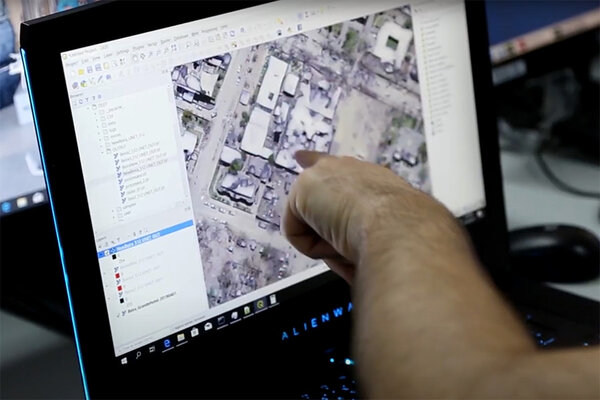

- DEEP (Digital Engine for Emergency Photo-analysis) is a machine learning application that automates the analysis of drone images. This speeds up damage assessments for large-scale emergencies, allowing the assessment of tens of thousands of structures in a few hours, compared to up to 2,000 a day using manual methods. When Hurricane Fiona tore through the Caribbean in 2022, WFP was able to scan and analyse the imagery in hours, whereas previously it would have taken up to three weeks. This allowed us to pinpoint the hardest-hit areas via a heat map and direct support faster than ever before.

- SKAI is an open-sourced tool that uses advanced machine learning to significantly accelerate post-disaster assessments and thereby response, providing critical insights 13 times faster and 77 percent cheaper than manual methods. It was developed by WFP in collaboration with Google Research and has been used in crises such as the Türkiye-Syria earthquakes in 2023 and Pakistan floods in 2022.

- The Enterprise Deduplication Solution uses advanced algorithms to address anomalies in WFP’s beneficiary databases, with an accuracy rate of 99.99 percent. The system has been piloted in three of WFP’s country offices, resulting in close to U$400,000 in savings. Independent assessments have confirmed it complies with global data privacy and security standards.

- SCOUT is a statistical-insights tool that supports key decisions by WFP on what to buy, where from, when, and how to store and deliver it to operations. In Western Africa, it meant savings of US$2 million for WFP in 2024 through longer-term sourcing and delivery planning of sorghum.

Challenges of using AI in regions with limited infrastructure or connectivity

Most of the communities we work with are in areas where there is limited internet and telecommunications access – even more so during an emergency. This is why tools like DEEP are so important, since drones for damage assessment don't need connectivity or sophisticated computer infrastructure. This accessible technology and offline availability is important since AI should not deepen the “digital divide” between richer and poorer countries.

Risks of using AI in the humanitarian sector

Data privacy is a prime concern, so it’s extremely important to put measures in place to ensure confidentiality when AI is used to process people’s personal information. There’s also a danger of bias – the use of models drawing upon incomplete data risks reinforcing existing inequalities rather than reducing them. People who should receive benefits could be excluded because they match a pattern of somebody who might not need them. This is why the use of interpretable models – where the reasons for outputs can be clearly understood by users – is important, especially in sensitive, high-stakes environments.

“AI should not replace the human element.”

Another risk is relying on results produced by AI without understanding the reasoning behind them. Humanitarians cannot afford to trust blindly a black box model, where systems' internal workings are not visible. AI can make mistakes and, even if results sound authoritative, they can’t be taken at face value. Humanitarians need to know why AI is making the calls and to sort what's good and bad data. As things evolve very fast in the world of AI, it is important to always keep reviewing how it is used, to ensure it remains relevant and safe. Ultimately, it is important that AI does not seek to replace the human element, but rather to enhance it.

And what are the opportunities?

A big opportunity lies in partnerships. Many private companies have already invested heavily in creating AI models and technology that can be used in the humanitarian sector, and even AI infrastructure like supercomputers – meaning powerful, high-performing models. There are also academic institutions doing research that can be applied. By partnering with others, humanitarians don’t need to reinvent the wheel.

WFP has launched its first Artificial Intelligence Strategy for using AI efficiently across operations and ensuring that people remain at the core of every response.

We are grateful to the following for their valuable contributions to this article: Magan Naidoo, WFP Chief Data Officer, Marco Codastefano, WFP Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence Consultant, and Patrick Mckay, WFP UAS data operations manager.