Feeding the future: Africa surges ahead on school meals

At Olympic Secondary School, in Nairobi’s informal settlement of Kibera, 17-year-old Mercy Mmboga carefully inspects the growth of young spinach leaves, arranged in rows of recycled plastic pipes in the school’s backyard.

“I learned about hydroponics in agriculture class. I was amazed,” she says of this soil-free farming method. “I can use a small piece of land to do agriculture.”

Twice a week, she and other Olympic students harvest the young plants, which provide a nutritional boost to hearty lunches served up to the school’s 1,200 students.

Not so long ago, the World Food Programme (WFP) would have been providing those meals. But since 2018, Kenya’s Government fully operates the national programme; WFP now provides only technical support, like installing the hydroponics infrastructure.

Under the Government’s leadership, school meals coverage has soared, reaching 2.6 million children last year, compared to 1.8 million in 2023. Kenyan authorities promise to scale up further, in line with a national strategy to provide universal school meals coverage, reaching 10 million children, by 2030.

Kenya’s success story reflects a wider trend. Worldwide, at least 466 million children receive school meals through government-led programmes, a 20 percent increase in four years. In middle-income countries, WFP has nearly halved direct school meals assistance, as national authorities increasingly take over.

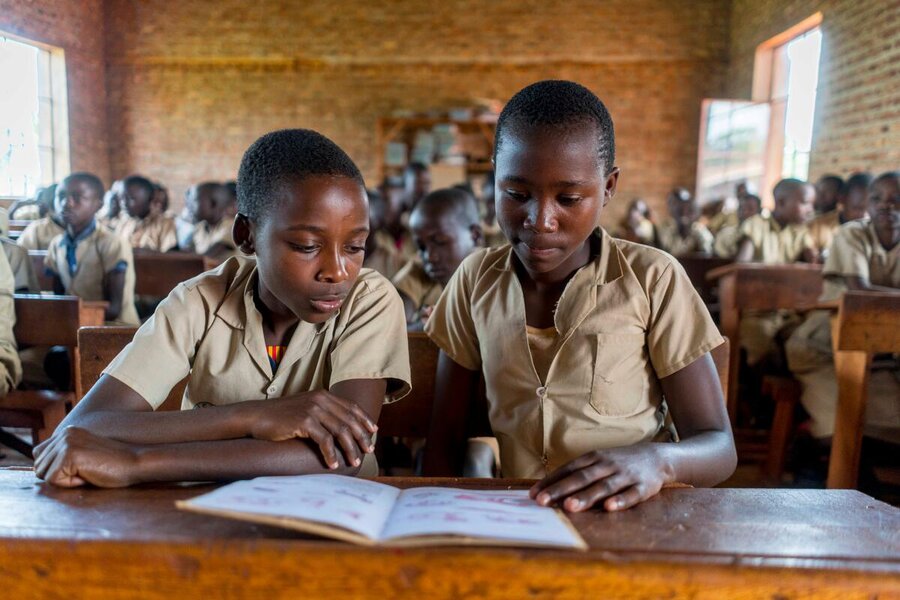

Sub-Saharan Africa is posting some of the most stunning achievements; 20 million more children are receiving school meals through government-led programmes than in 2022. Continent-wide, 71.5 million students benefit from hearty meals or snacks, as authorities increasingly recognize them as vital investments in children’s health, education and national development.

“Leadership in Africa has really stepped up,” says WFP School Meals Director Carmen Burbano, highlighting not just Kenya, but also other major achievers, including Rwanda and Benin. “It’s a matter of political will,” she adds of school meals. “It’s a matter of a programme that everyone now knows works, that is an established policy. Leaders are responding to it in such an important way for kids in those countries.”

In countries like Burkina Faso, Lesotho and Rwanda, school meal programmes are today mainly funded through national budgets. Others, including Ethiopia and Burundi, have doubled or tripled their school meals investments since 2022, while still receiving some external funding.

“Government takeover is a success story,” says Edna Kalaluka, Head of School Feeding at WFP’s Eastern and Southern Africa regional office. “It means we are meeting our goals. Government ownership promotes sustainability.”

Beyond the plate

In Kenya, the strategy is not just to scale up school meals: the government also aims to embed planet-friendly practices - like hydroponics - into the programme, and to strengthen local food systems. WFP is assisting these initiatives, where food is grown at school, or sourced from local farmers. Findings show this strategy can generate between US$7 and US$35 in economic returns for every US$1 invested. Last year, Eastern Africa alone sourced over 32,000 metric tons of food from over 18,000 farmers, injecting nearly US$16 million into local economies.

At Olympic school in Kibera - one of Africa’s largest informal settlements, where child malnutrition is high - the WFP-supported hydroponics scheme allows students to grow vegetables more quickly than with traditional agriculture. Hydroponics also demands far less water, in a country experiencing recurrent droughts. Some Olympic students, like Mercy, now want to become farmers when they grow up.

“These greens help us get the nutrients to concentrate in class and learn,” says Mercy of the vegetables, planted in old yoghurt containers. “I can recycle the plastic,” she adds. “It’s good for the environment.”

Elsewhere in Africa, locally sourced school meals are also gaining ground, providing powerful arguments for countries whose agriculture depends on smallholder farmers. That’s the case of Rwanda, where the country's 4.5 million young pupils all receive school meals.

Growers like Clementine Mukandayisenga, in Rwanda’s eastern Kayonza district, are central to that strategy. A member of a WFP-supported farmers’ cooperative that supplies her children’s school with fruits and vegetables, she has just harvested a fresh batch of amaranth, a nutritious plant.

“The fact that my children eat at school has been very beneficial to them. I see this from their report cards,” Mukandayisenga says. “By selling to schools and markets, my husband and I were able to save and buy a plot of land.”

In neighbouring Burundi, locally sourced school meals boosted farmers’ incomes by 50 percent in 2024 and generated jobs in dozens of cooperatives.

In Benin, where the government has also assumed ownership of the school meals programme - and where area growers similarly provide the ingredients - Schékina Ahanhoto says the food helps her learn. “I know that when I eat my canteen meal, I'll be in good health and I'll be able to keep up in class,” says the nine-year-old, who wants to become a judge.

In southern Malawi, a country where studies show every US$1 spent on school meals generates US$8 in benefits, headmaster Felix Malinda says students once dropped out because of poverty and hunger. Now, with the farmer-supplied meals, he says, “we have noticed that the enrolment of the school is growing.”

Adapting to crises

Despite these strides, challenges remain in ensuring Africa’s students get the meals they need. In some African countries, conflicts, funding cuts and access constraints have forced WFP and governments to sharply shrink coverage for pupils, and sometimes seen schools shutter altogether.

That’s the case in Sudan, where an ongoing civil war has forced some 16 million children out of school and massively disrupted food supply chains. Even so, more than half-a-million students benefited from locally procured school meals last year — with WFP buying US$6 million in cereals from local farmers.

In the small town of Al Hafayer, in eastern Sudan, schools have closed but learning has not ended. Nor have school meals; children instead receive WFP’s take-home rations. On a recent day, dozens of children gathered for their morning singing at an abandoned hospital turned makeshift school. Many came from a nearby camp housing conflict-displaced Sudanese.

“I believe the current generation needs a good education to progress and benefit their country, community and family,” said teacher Hassan, who leads the singing. Uprooted by fighting, he counts among a group of volunteers now teaching the children. (WFP is not using his last name for his protection).

Another volunteer teacher, Hanaa, from the city of Sennar - roughly 600 km away - is similarly determined to give Sudan’s next generation an education. “It's important for students to have sufficient meals,” she says, “because if they're healthy, they will understand everything they're taught.“

Lisa Murray, Bismarck Sossa, Giulio d'Adamo and Abubakar Garelnabei contributed to this story.

WFP's school feeding programmes in Africa are supported by donors that include the African Development Bank, Burundi, Education Cannot Wait, France, Japan, Kenya, the Republic of Korea, Share the Meal, the UN Multi-Partner Trust Fund Office and the U.S. Department of Agriculture McGovern-Dole Food for Education and Child Nutrition Program.

Learn more about WFP's work in Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Rwanda and Sudan