The food safety ‘gatekeeper’ who missed meals as a child in Kenya

Caroline Mwendwa didn’t always have access to safe or nutritious foods as a child growing up in rural Kenya. This is partly what inspired her to become a food technologist with the World Food Programme (WFP), dedicated to ensuring that no adult or child gets sick because of eating contaminated food.

Tell us a bit about yourself

I was born and raised in Kitui County, a semi-arid region in south-eastern Kenya. My father was a teacher and my mother a housewife raising five children. Growing up droughts were common, food was scarce, and we often went to bed hungry.

The Government provided relief food for our community from time to time, but it was often poorly stored under a shed at the local administrator’s office.

So food was exposed to weather elements, pests and rodents. We didn’t know it then, but this food was further compromising our health... but we had no other option.

Back then, our parents knew little or nothing about food hygiene and food safety. As a result, I often suffered from bouts of food-related diseases such as food poisoning and missed many days of school.

From an early age, I was inspired to pursue a food-related career. While in high school, I listened to a career talk from a food scientist and I knew instantly that I wanted to become a food technologist. I wanted to educate my community on food safety and sustainable agriculture.

What does being a food technologist in Kenya involve?

My role is to ensure that all the food that WFP provides is safe for human consumption. For example, suppliers must adhere to certain food standards during production; local farmers must uphold good agricultural practices while growing food, and we at WFP need to ensure that those who receive our food know how to safely prepare their meals.

Each month, WFP distributes food to around 430,000 refugees and another 390,000 Kenyans receive food rations during the lean season. Annually, we support around 100,000 children aged under-5 with nutrition supplements and an equal number of pregnant or breastfeeding mothers.

If we didn't rigorously check the food, people would get sick or die. We cannot let that happen.

What keeps you up at night?

As the “gatekeeper” for food safety and quality, I have rejected food from smallholder farmers because it didn't meet the necessary standards. It breaks my heart because I know the struggles that farmers go through only for their food to end up in a landfill site.

In these cases, I am seen as the villain who denies farmers their hard-earned income.

I recently visited a farmers group in Western Kenya. Most of them were widows and they had aggregated their maize in readiness to sell to WFP. Immediately, I could tell that the maize was discolored and mouldy , which indicated possible aflatoxin contamination. When the tests came back my fears were confirmed. Out of 1,500 mt, only 660 mt was fit for consumption.

Breaking this kind of news to farmers is never easy. The phone calls that follow are unbearable. That is why it is so important that we support programmes that educate farmers, so we can avoid such heartbreak.

What keeps you going?

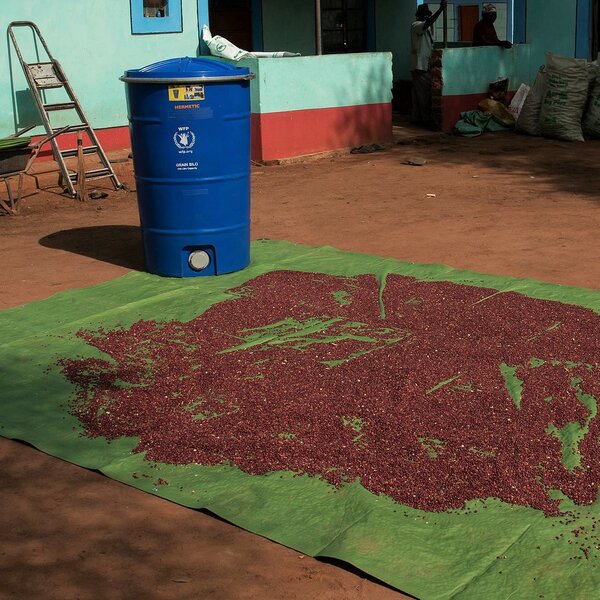

We have an incredible opportunity to build the skills of all food producers, especially smallholder farmers. WFP trains farmers to harvest, dry, and store their crops immediately after harvesting to avoid contamination from pests and mould. We also promote the use of affordable technologies such as tarpaulins for harvesting and drying and airtight bags and silos for the safe storage of harvested crops.

The smile of a farmer whose crops have met our food safety standards is deeply satisfying.

Kenya has strong rules and regulations about food safety and quality, but many consumers either don't know about them or follow them. Part of my job is to train farmers, traders, public health officers and consumers on food safety and quality. I enjoy teaching and advocating for awareness on food safety to all stakeholders in the food supply chain.

As a result of my efforts and WFP's commitment to food safety and quality improvements, I am certain that people in the arid and semi-arid counties (including in my village) will no longer be exposed to health challenges caused by the consumption of contaminated food.

This is my contribution to WFP's goal of saving lives and changing lives.