Interview: How school feeding took over the world

That 466 million children now receive school meals through government-owned and managed initiatives worldwide – as a new report reveals – is music to the ears of Carmen Burbano.

“An increase of 20 percent over the past four years is remarkable,” says the Director of School Meals and Social Protection at the World Food Programme (WFP). “That’s 80 million more children.”

One factor in this success is the launch of the School Meals Coalition in 2021 – with backing from France, Finland and Brazil – in the thick of the pandemic and the “biggest hunger-and-education crisis in history”.

“Schools closed, programmes collapsed and governments realized how important these meals were,” Burbano recalls – 370 million children had lost access to nutritious school meals.

Initially, around 40 countries signed up to the WFP-supported Coalition where the organization works alongside UN sister agencies UNICEF, UNESCO, IFAD, WHO and FAO.

More than 100 countries are now signed up. The Coalition has succeeded in the key objectives of restoring all the national programmes toppled by COVID-19 and is now going even further in expanding coverage.

“Throughout the shock of lockdowns and economic downturns, governments continued to invest in school meal programmes,” says Burbano.

The latest State of School Feeding Worldwide report is proof that: “If you decide a school meal programme is important, you can roll it out in one or two school years and really see the benefit of your work.”

From aid to development

For most of the 20th century, “the development community typically viewed school feeding as simply about delivering food aid”, says Burbano.

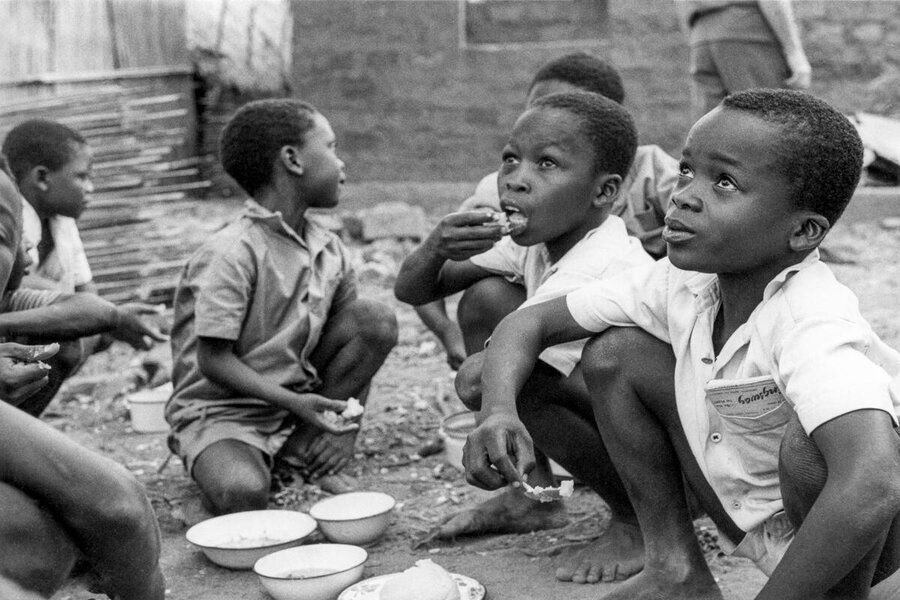

In 1963, the newly launched WFP ran its first school meals initiative in Togo. Over the decades, its coverage spread across the world, but it was not until the early 2000s that school meals and development joined forces.

“Twenty years ago, school meals were often treated as small projects, essentially a way to use up excess food aid,” says Burbano, who joined WFP in 2004.

“The big question then was sustainability – how to make sure these programmes were embedded into national policies, into what governments do and pay for, and then how WFP could support that process.”

Humanitarians required a change of approach to achieve the end goal of “sustainable national school meal programmes that don’t need us anymore” – along with a dose of patience and commitment.

For a government to fully take over school feeding, it can take up to 15 years.

In Kenya, “the Government took over full implementation of school feeding support in 2019 after 10 years of planning ,” says Burbano.

“Around 50 governments are now running their own national programmes, after receiving WFP support – I’m proud of that.”

Political will

Having grown up in Ecuador as the daughter of a teacher, “education is in my DNA,” says Burbano. She is acutely aware that the promise of children receiving a meal at school serves as an incentive for parents to ensure attendance.

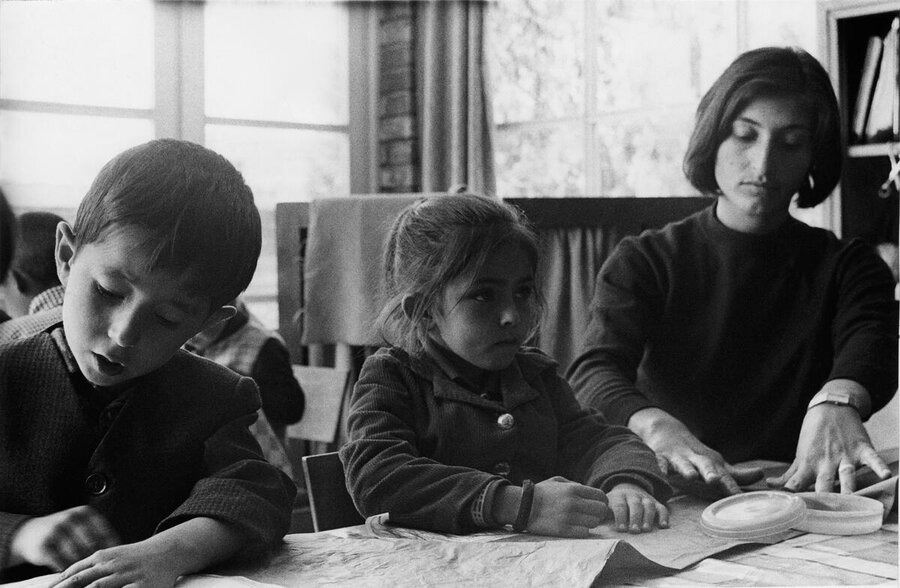

She emphasizes that in providing the nourishment children need to learn better school feeding programmes “are never just a plate of food, they are a platform” for development.

Delivering on long-term potential takes “working with governments, shifting gear, being thoughtful, planning”.

The State of Schoool Feeding report confirms a generation of children is benefitting.

“By investing in children very early, you’re also figuring out how they’re going to be healthier adults in the long run,” says Burbano.

Impressively, 99 per cent of financial investment in school meal programmes comes from national governments, a measure of how the pandemic galvanized countries’ intentions.

“Low-income countries that face the most problems in financing are the ones making the most progress,” says Burbano.

In the past two years, an additional 20 million children in Africa have received school meals through government programmes, with a total of 71.5 million children served.

“Clearly, it’s a matter of political will. It’s a matter of a programme that everybody now knows works.”

That certainly explains why global funding for school meals has almost doubled, from US$43 billion in 2020 to US$84 billion in 2024.

Farms and communities

An essential pillar of school feeding today is the concept of “home-grown” school meals.

In the early 2000s, home-grown was touted as a “win-win” for agriculture and education – locally grown and procured produce that strengthens farmers, communities and food systems.

But it took a long time for it to become the force it is today, Burbano says.

While home-grown school feeding is not a one-size-fits-all recipe for sustainability within countries, 70 per cent of the food governments buy goes to schools.

“That’s a huge market and an enormous opportunity to support the local economy.”

The financial crash of 2008 set the wheels in motion as many governments faced pressure to scale up support for vulnerable families hit by the global downturn. In response, WFP and its partners started exploring ways to buy more food locally and tie school feeding to local production.

But unlike today, “the mechanisms were not in place to dispense cash so that schools could buy vegetables, fruit, eggs and more.” WFP’s systems, geared to emergency response, “simply didn’t allow it.

Much had to change before WFP’s country offices could start experimenting and responding to what the governments wanted. “It’s not until you have the hard data and the hard results that you can really get policymakers to respond and donors to support,” says Burbano

A huge opportunity

During the 2009 food and fuel crisis, the World Bank set up its Global Food Crisis Response Programme to assist lower-income countries. To its surprise, many used those funds to expand school feeding. That was when the Bank reached out to WFP.

“I was tasked with collaborating on what would be the first serious analysis of school feeding,” says Burbano. What began as “guidance notes” ended up as a landmark report, translated into seven languages.

Indeed, Rethinking School Feeding: Social Safety Nets, Child Development, and the Education Sector proved pivotal – “the first comprehensive look at school feeding, framing it, for the first time, as a serious investment for governments and donors.”

The book formalized the potential of school meals as a game-changer for the Millennium Development Goals (which preceded 2015’s UN Sustainable Development Goals).

“We showed how school meals could serve as safety nets, supporting education, health and nutrition, while also benefiting local markets.”

Taking its cue from the document, as governments requested further support, WFP put in place its first school meals policy in 2009, updated in 2013, to guide efforts. “It was a big shift for WFP, but we knew it was needed,” says Burbano.

But there were still evidence gaps. A research agenda was established to address questions. “The big missing piece was learning. Did school meals actually improve learning? That evidence has taken 15 years to build.”

Feeding the future: Africa surges ahead on school meals

With this latest report, “we can show school meals are one of the most important tools for learning, outperforming many traditional education strategies,” says Burbano.

The other gap was whether the programmes really increased the incomes of farmers and provided local jobs. “In the new report, we are announcing that yes, school meal programmes employ around 7.4 million cooks, most of them women,” says Burbano

“It has taken us a long time to get here, but we're here. Governments are leading, the international community is starting to move, and WFP made this a priority.

She adds, “Even with all this progress, there is so much more to do. Low-income countries need much more support from all of us. Only 30 percent of kids in low-income countries have access to these vital programmes, compared to 80 percent of children in high-income countries. We can and must do better.

“Twenty years ago, when I started at WFP, I fell in love with this programme because I saw that it had the potential to change the future for millions of children, families and communities. We’ve come a long way and have much to celebrate as we launch this new report. We don’t see successes like this these days. But we’re not done. I’m not done. I will continue to dedicate my career to this cause.”