Orange parachutes rain down from a blue sky

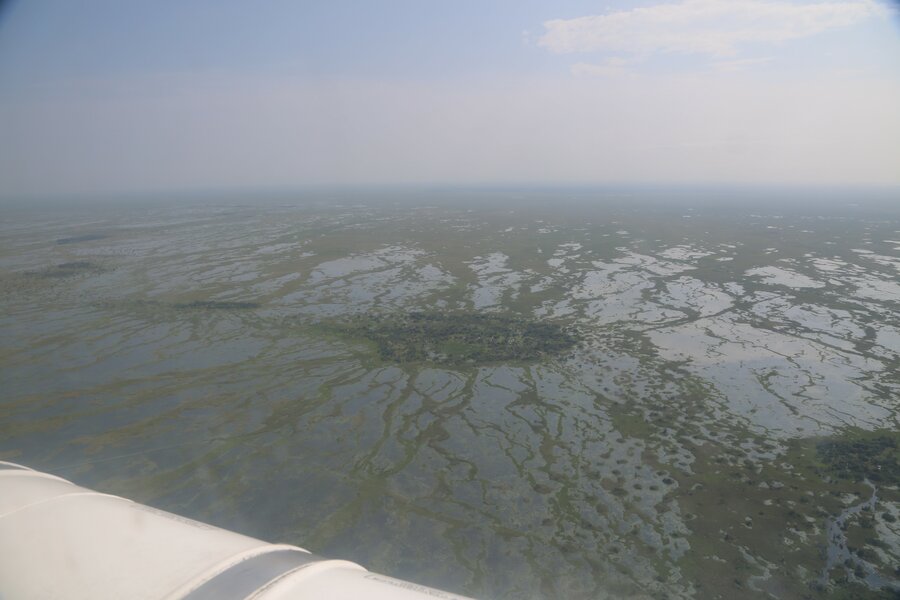

From the air, the water stretches in all directions up to the horizon across the still vastness of South Sudan. To the people who struggle to live here, the marshes at times of conflict provide an element of protection, but also pose a challenge.

People cannot reach the town of Nyal bordering on the South Sudan marshes by road, so they have to take small canoes and risk attacks. Nyal is accessible by air, but its grass airstrip isn't big enough to take the planes that can carry the amounts of food assistance that some 30,000 people need on a daily basis.

So the World Food Programme (WFP) has no choice — both in Nyal and many other places in South Sudan, especially during the rainy season. WFP can only bring food to the most vulnerable people by air. And for it to be delivered without aircraft landing, food has to be dropped from the sky when possible.

"It really is a sight to behold," said WFP South Sudan Country Director Adnan Khan. "Airdrops of food during the rains when much of the country is cut off from land access are absolutely essential to keep people fed in hard-to-reach areas."

"Airdrops are a key part of WFP operations in South Sudan. Donors support them precisely because they keep people alive in the most isolated areas," he added.

The 1,000-metre-long airdrop zone at Nyal was underwater for a week so all food flights there by the World Food Programme were cancelled. Today, however, it has reopened because the water receded and the ground has dried out.

The Mi-17 helicopter bringing us clatters over the town. But most people pay little attention as it lands on what is perhaps the Nyal's biggest asset in the rainy season: a large meadow for livestock that also functions as a drop zone when necessary and is marked with a big white X in its centre as the target.

In nearby tukals or traditional mud huts with grass roofs in compounds ringed by thorn fences, children play games while their mothers prepare what food they have for the day or tidy up. Men stop to talk on corners or stroll around.

The children beam with smiles as they follow newcomers through Nyal in Panyijar County, the southernmost in Unity State. Early this year, it had levels of hunger among children under five years of age that were more than twice the emergency threshold. But at the same time, experts forecast that Panyijar could avoid a famine declared in two other counties — if humanitarian assistance for the weakest was delivered as planned in the coming months.

The famine declaration in South Sudan and simultaneous warnings of looming famine in three other countries were unprecedented. The one factor common to all four countries was protracted conflict, which steadily ate away at the ability of tens of millions of people to feed and support themselves.

South Sudan, which won independence in 2011 from Sudan after decades of civil war, was already among the world's least developed countries. Most people already had little to survive on when fighting broke out in the world's newest country in December 2013.

At one time more than 60,000 people affected by conflict were receiving food assistance in Nyal. But due to improvements in security as well as a registration process that allows WFP to pinpoint who exactly is eligible to receive food, the number being assisted had been cut to some 30,000 people.

The noon calm is broken by whining jet engines powering a WFP-contracted transport plane, which flies up from the South, over the town and returns on a dry run along the drop zone as people are told by monitors to stay clear.

Most people are used to what happens and sit and watch as the plane flies round Nyal and then turns back to the South. At a set point, the pilot opens the rear doors, pulls up the nose and increases the power, sending red plastic bags of beans falling from the sky to the ground.

The aircraft slowly completes three more drops, takes one last run down the zone to check their accuracy and then turns back to the South Sudan capital Juba. As soon as it disappears, dozens of men and women rush in and start collecting bags and piling them at distribution points outside the drop zone.

The bags are heavy — 50 kilogrammes each — but are collected quickly as the people know that more airdrop aircraft are on the way. This time it is a plane from Entebbe airport in Uganda loaded with maize and vegetable oil.

In 2015, WFP in South Sudan carried out its first successful airdrop globally of vegetable oil. Previous trials failed because containers broke on impact with the ground. The secret to success proved to be packing up to six bottles of oil in a plastic box with padding and attaching a small parachute to each box.

This innovation means WFP can deliver by airdrops all the foods it supplies when necessary. So places unreachable by road or water receive their basic food needs, at lower costs, compared to when aircraft had to land to deliver vegetable oil.

People, mainly women, collect the food — cereals such as sorghum and maize, lentils, beans, special fortified foods and the vegetable oil. Groups of four or five families receive one combined allocation and divide it among themselves.

"We've been watching this very intricate but very well organized process that these women have of distributing rations to make sure that everybody gets their fair share," said Valerie Guarnieri, WFP Regional Director for East and Central Africa.

"As the World Food Programme, and with our partners, we're really happy to be able to be part of helping the people of South Sudan," she added.

How can you help? Make a life-saving donation today to keep WFP delivering food to those in desperate need and help us in our campaign to fight famine. Visit facingfamine.org to learn more.