War on hunger grinds on amid glimmers of peace in South Sudan

Streets in South Sudan's capital Juba are aptly named: CPA, Addis Ababa, Referendum, Independence and Unity. Juba City Council says that these echo the main milestones in the country's history since 2011.

CPA is short for the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement that sought to end the Second Sudanese Civil War. Several peace agreements were brokered in Addis Ababa only to be broken. But the Ethiopian capital's contribution is not ignored.

"I hope that one day, we can drive down Peace road," says Deng Kiir Malong, 35, a school teacher by day and taxi-driver by night, at weekends and on school holidays. Malong is not at all alone in his dreams for a peaceful future.

Some 200 km north of Juba, in the ramshackle town of Bor, Ayen Kelei, 30 and a displaced mother of six children, still hopes for the same.

"I pray for peace every morning when I wake up and at night before I go to sleep," she says. The Gods might, perhaps, have answered her prayers.

Guns fall mostly silent

A September 2018 peace agreement seems to be holding amid signs of detente between the two main warring parties. Giant billboards preaching peace have mushroomed along city streets. Though gun-toting soldiers still patrol main roads and checkpoints remain along busy roads, the guns have largely gone silent across much of the country. At least for now.

But the war against hunger rages on.

Grim outlook for increasing hunger

Half the population of 11 million faces severe food shortages between now and March 2019. Some 5.3 million people like Ayen need food assistance now to survive. Analysts say the situation might get even worse before it gets better.

"More and more people are likely to struggle to put food on their tables especially as the country approaches the peak hunger season between May and August 2019," says Simon Cammeelbeeck, Acting Country Director for the World Food Programme (WFP) in South Sudan

A new United Nations report analyzing food security in the country , called the Integrated Food Phase Classification (IPC), confirms this. The report, released on 22 February, indicates that close to 7 million people — or 60 percent of South Sudan's population — will be unsure where their next meal will come from at the peak of this year's lean season.

"The report indicates the severity and magnitude of food insecurity in South Sudan this year," says Cammelbeeck. "But we expect the lean season to start much earlier than usual because of a particularly bad 2018 growing season."

WFP is preparing to respond to the needs of 5.1 million vulnerable people in the country and is prioritizing its assistance to those areas in greatest need.

Tough times remain ahead

For most South Sudanese like Deng and Ayen, tough times persist and they are not likely to improve any time soon.

After a lifetime of trauma, Ayen fled her homestead six years ago, when fighting engulfed Maar, a village a stone's throw from Bor.

Carrying her few possessions, she arrived in Bor with hopes of returning home as soon as the situation returned to normal. But how soon is soon? Days gave way to weeks, which turned into months, which became years.

Fighting has now reduced, but Ayen has not returned home. Without firm assurances of her children's safety, she has decided to stay put.

"I would like to go home and continue with farming, while my children go to school, but I can't because of insecurity," she says, glancing at her youngest, a three-year-old girl who seems never to leave her side.

It is almost as if the child somehow knew that her life now depends solely on Ayen, following her father's death a few weeks after she was born.

Home for Ayen is now a distant memory of what seems a glorious past. "I was independent, I was happy and produced a variety of crops," she says.

To survive, she now farms the garden behind her shack and rears livestock. She produces vegetables and crops such as maize. Whatever she harvests is augmented with food assistance. If she gets a surplus, she sells it at the local market.

Enough food for one month

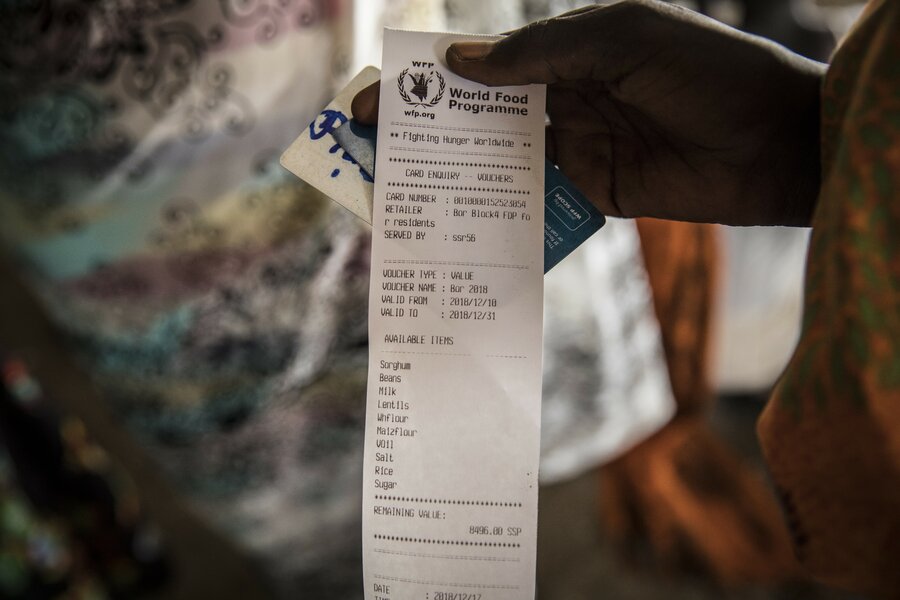

WFP provides an electronic voucher loaded with the equivalent of US$50 in local currency for the family of seven. Ayen redeems the voucher at a store for sorghum, maize flour, beans, sugar, lentils, powder milk, salt, rice and vegetable oil — enough to last the family for one month.

WFP's response across the country

With her food needs taken care of, she is able to send her children to school with the proceeds that she makes from her own thriving vegetable garden.

WFP provides life-saving food distributions to the most vulnerable people, along with food in return for work to construct or rehabilitate community assets, food for school meals and special products for the prevention and treatment of malnutrition in children, and pregnant or nursing women.

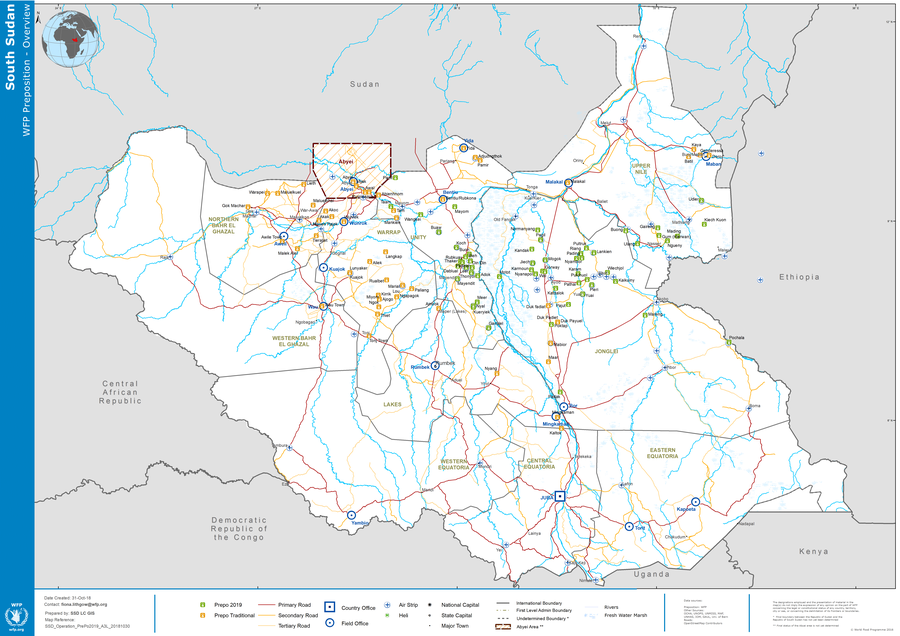

WFP is also currently stocking up food supplies in more than 60 sites throughout the country before the onset of the rainy season in May.

The food is purchased, transported, and stored while roads can still be used for deliveries and it is then distributed through the rainy season, which coincides with the peak of the lean season, the hungriest time of the year.

"Pre-positioning food by road will reduce the operational costs for WFP by as much as US$100 million because we will not have to resort to the much more expensive alternative of airdrops to get food in," says Cammelbeeck.

Comprehensive response

Since 2014, WFP and key partners have been pioneering an Integrated Rapid Response Mechanism (IRRM), where mobile teams reach people in remote, isolated areas. Traveling usually by helicopter and sleeping in tents, teams register people in need so WFP can transport food, nutrition supplies and other assistance by road, river or airdrops where there is no alternative access.

WFP is also scaling-up the use of cash transfers in locations with functioning markets. In 2018, WFP disbursed over US$27 million in cash to 660,000 recipients monthly. This gradually increased the inflow of much-needed cash into local economies.

But to mount an effective response in South Sudan, WFP needs above all resources.

Funding for the coming months

"Donors have been supportive," says Cammelbeeck. "WFP appealed to donors for US$662 million in late 2018 and we have received more than half of the required funding." WFP is now appealing for a remaining US$215 million to provide much-needed food and nutrition assistance until July this year.

"Without this, millions of hungry people will be cut off from deliveries by road so we might be forced to use costly airdrops to provide assistance," he adds.

As the warring parties in South Sudan's long and brutal war have moved to make peace, much to the delight of many people like Deng and Ayen, WFP and other humanitarian organizations still need support to continue the even longer war against hunger in one of the world's least developed countries.