Why Project Amata is good news for school meals in Burundi

“The house I have, it came from milk production,” says Isaac, a dairy farmer in Bugendana, in Burundi’s central Gitega province. “When I had no cow, I was living in poverty.”

The livelihoods of Isaac and his wife Bernadette depend upon their cows and the milk they produce. And that milk also helps support other households in the community. “Those with small children sometimes come to us”, says Isaac, “and ask for half a litre, or a litre, for their baby.”

Le grand revers: comment le coronavirus a renvoyé les écoliers affamés à la maison

Burundi is currently the country with the lowest frequency of milk consumption in East Africa — around two cups a month per person. It’s rarely available and, when it is, it’s a luxury.

Building on the success of Project Leche in Honduras, the World Food Programme (WFP) and Kerry Group, the global taste and nutrition company, are empowering smallholder farmers like Isaac and Bernadette through Project Amata, which launched in January (amata is the word for milk in Kirundi, the national language of Burundi).

Working closely with farmers, milk collection centres, and others, the project is providing much-needed equipment and training, covering key areas of livestock management and milk production — from how best to feed and tend to cattle, to processing and distribution.

“May you have cows and children,” is a common blessing in Burundi. Cows, with their milk, butter and cheese, offer a lifeline for the most vulnerable, providing the nutrition and income people need to raise – and feed – their families.

But in a country with the second-lowest GDP in the world, nutrition and income are often lacking. Today, chronic malnutrition affects over half of Burundi's 11 million people, with many living below the poverty line.

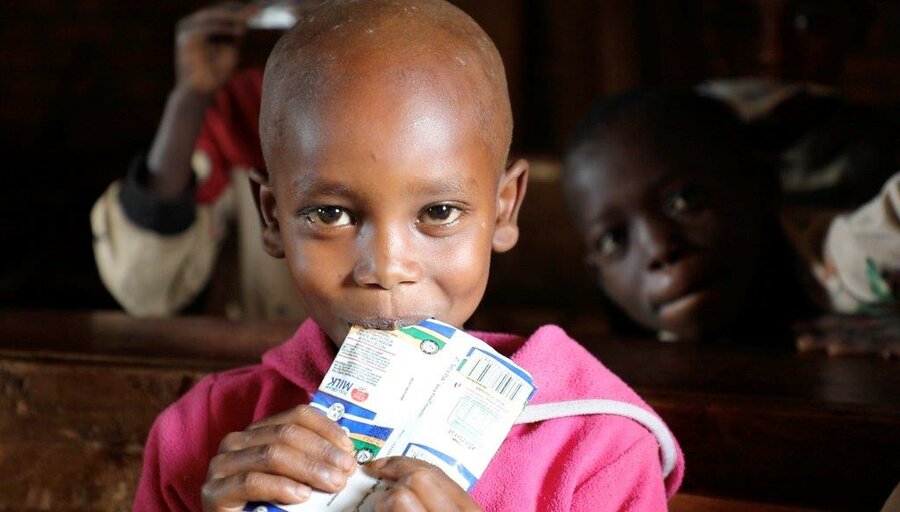

The impacts are devastating, particularly on the young. Malnourished children are more vulnerable to infections, while their performance at school is seriously undermined.

Too valuable to be a luxury

WFP assists more than a million people across the country, half of them schoolchildren. However, needs are huge and there are still “many students who do not eat in the morning, before coming to school,” says Liberté Bigabwa, director of an elementary school in Bugendana. “When they don't have food or milk here at school, it becomes a problem for us to keep them focused.”

Although the WFP School Feeding programme is an incentive for children to attend, “some drop out because they do not have enough to eat,” Liberté adds. Schools that are not supported by WFP see much higher dropout rates.

Milk is one of the few sources of animal protein available to children in Burundi. It also helps combat stunting, a cruel condition linked to malnutrition that caps individuals’ potential to thrive, by limiting their physical and cognitive development. That’s why Project Amata, building on previous WFP projects, will also engage schools and local communities, making milk more accessible for thousands of students and raising awareness about its importance in curbing malnutrition.

Big challenges for smallholders

Life on a smallholder dairy farm is tough. Isaac and Bernadette wake up before dawn every day to tend to their cows. Work is hard, but challenges often arise from a lack of tools and expertise, rather than the long hours.

This is particularly true when it comes to hygiene: at times, despite their best efforts, their milk doesn’t meet the required hygiene standards, and milk collectors can refuse to buy it. This means lower income for Isaac and Bernadette, and less milk available to those who need it.

But there are other difficulties, too. Unlike thousands of farmers in Burundi, Isaac and Bernadette have yet to receive support and training from WFP, and they simply don’t have the means to increase production. These include more — and better quality — fodder for the cows, as well as storage space to get them through the dry season.

“We need to learn the techniques to feed cows throughout the year,” says Isaac. That’s precisely the kind of knowledge the project is seeking to equip 1,000 farmers with — including Isaac and Bernadette. And Kerry, by sharing its dairy, nutrition and processing capabilities, is the perfect partner for the challenge.

But even with increased yields, farmers are often undermined by the next step in the chain — transport.

Transport: a weak link in the value chain

In Burundi, milk mostly travels on bicycles. From farms to milk collectors, from collectors to processing plants, even from vendors to buyers — milk is often transported in unhygienic conditions, sloshing around for hours inside overheated containers fastened to the bicycles.

Up to 80 percent of all milk bought in Burundi is sold by roaming bicycle vendors. And their milk is often unsafe for consumption.

Farmers have to rely on bikes, too. Using what containers he has, Isaac transports his milk to a local collector. The collector then tests the milk and, if acceptable, loads it on his own bike, to deliver it to the collection centre.

“The journey is long,” says Isaac, “it takes more than two hours. This often spoils the milk before it is even put in a refrigerator.”

So if Isaac and Bernadette’s milk is accepted by the collector, it could still be rejected by the collection centre itself. But it is often impossible for farmers to pinpoint which, along this long faulty chain, is the weak link.

That’s why Project Amata will work to identify — and supply — equipment for farmers and collectors to transport milk safely, building strategically on previous WFP and partners’ milk projects in Burundi.

Capacity, safety standards, transport, availability: Project Amata aims to enhance all these aspects of milk production, to help fight malnutrition among the 130,000 people of Bugenada, and beyond.

How to address these challenges is a complex question — but one thing’s for sure: milk and dairy farms like Isaac and Bernadette’s are part of the answer.

Supporting those in need — together

“Project Leche helped bring safer, more nutritious meals to thousands of school children in Honduras,” says Housainou Taal, the WFP Representative and Country Director in Burundi. “Equipped with Kerry’s unparalleled expertise in the area of sustainable nutrition, and following WFP’s previous work on milk production in Burundi, we can replicate those results here, improving the diets and lives of schoolchildren, farmers, entire communities.”

“We are delighted to be able to share our dairy, processing and nutrition expertise on Project Amata. This is an example of how Kerry, WFP, and local agencies can work together towards achieving Sustainable Development Goal 2: Zero Hunger. It also provides a further concrete example of our Better for Society social impact programme in action, helping to improve the health and nutrition of people in need,” says Edmond Scanlon, Kerry Group CEO.

Find out more about WFP's work in Burundi.