From Kansas to Kakuma: how US wheat helps power humanitarian aid

Doug Keesling’s wheat field in Chase, Kansas - America's 'wheat state' - stretches as far as the eye can see, the young plants beginning to sprout ears of grain. But their green promise is deceiving. Keesling, a fifth-generation farmer, is worried.

“We’ve had plenty of sun,” he says, “we need rain now. We’ve been in a drought.”

Thousands of kilometres away in northwestern Kenya, refugee Waad (whose surname has been withheld for her protection) is no stranger to drought. But it was conflict, not climate, that uprooted the 27-year-old from her home in Sudan’s Nuba Mountains.

Now a mother of three, Waad lives with her family in a small blue-and-white tent with iron sheeting at the sprawling Kakuma refugee camp. Most of its 300,000 residents depend almost entirely on World Food Programme (WFP) rations to survive.

“The food from WFP is the only thing most of us know,” Waad says.

The connections between Kansas and Kakuma are forged by hunger - and by the Midwestern state’s long legacy as an agricultural powerhouse. On any given year, Kansan farmers like Keesling grow nearly one quarter of America’s hard red winter wheat, a leading grain included in WFP’s assistance to refugees and other vulnerable groups.

Kansas and Kakuma are also connected by history. In 1953, Kansan wheat farmer Peter O’Brien floated the idea of using surplus American harvests to feed hungry nations – and open new markets to American growers. It sparked the birth of food assistance in the United States. Less than a decade later, WFP was founded.

“It’s a history that our farmers are very proud of,” says Justin Gilpin, Chief Executive Officer of the Kansas Wheat Commission. “They’re proud of knowing they help to feed people and develop goodwill around the world. And in having a mechanism like WFP that can get the commodities to hungry people in challenging situations in a very responsible, efficient and accountable way.”

Saving lives

Wheat farmers count among a raft of American growers traditionally powering WFP’s food operations. In Western Nebraska, the New Alliance cooperative packages, bags and ships commercial but also US Government-procured dry beans for WFP and other humanitarian operations in places like Haiti and African countries.

“For our Nebraska farmers, the main intent is to make a profit from their product,” says Dave Weber, manager of the enterprise representing more than 250 area bean growers. “But they all really appreciate the fact their beans may save people’s lives.”

The US Government-purchased food gets to the people WFP serves via multiple routes. Keesling’s wheat, for example, is moved by rail to the Houston or Galveston ports in Texas, before being loaded onto cargo ships for the roughly six-week journey to Mombasa – home to East Africa’s largest port.

“We’re covering all the region,” says WFP Mombasa field office head Emilie Dufour, referring to the nine countries in Eastern Africa where WFP works. The wheat and other US aid - including yellow split peas, rice, lentils and cornmeal - also supports our food assistance beyond the region, including in Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar and Togo.

The Kakuma-bound wheat undergoes another quality inspection in Mombasa, before it is loaded on trucks to the refugee camp, more than 1,200 km away.

“It doesn’t stay long once it gets there, because the food is programmed for monthly distributions,” says WFP logistics officer Jairus Mutisya. “So it moves quite fast.”

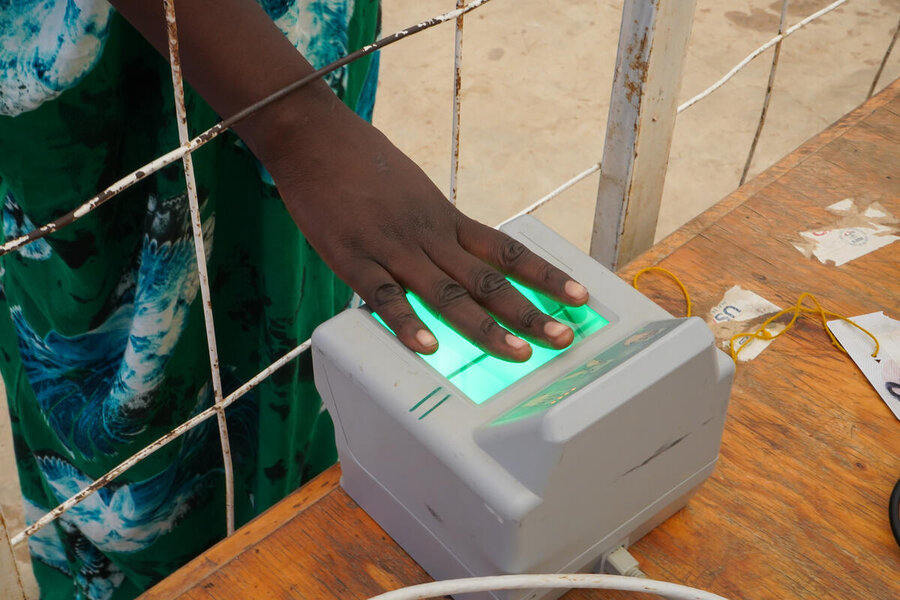

In April, the Kansas Wheat Commission’s Gilpin joined US farmers visiting Kakuma to see WFP’s operations firsthand – and understand where their harvests end up.

They also saw the local fallout of sharply shrinking international aid: that translated into a 40 percent cut in WFP’s food assistance to Kakuma’s refugees. Without more funding, the refugees will receive even less: just 28 percent of their daily recommended rations from June. Small bags of rice and other commodities are on display to visitors, showing what a monthly ration means for a family of five.

“It was really impactful to meet with refugees and hear their stories of what humanitarian assistance has meant to them,” Gilpin says. “And the challenges they now face with the ration cuts.”

Building self-reliance

Sudanese refugee Waad describes the WFP support as “the only lifeline” available for families like hers. But with ongoing cuts, she must find other ways to feed her children.

“I started keeping chickens, just a few at first,” she says. “Sometimes we sell eggs, sometimes a bird or two. It’s small, but it helps.”

When the US wheat farmers visited Kakuma, Waad was struck by their sincerity. “They encouraged us to farm,” she says.“WFP has talked about support in building self-reliance. If that means helping me to grow my poultry business or do vegetable farming, that will really help.”

Waad arrived in Kakuma a decade ago, as bombs fell and fighting escalated near her home in the south of Sudan. She and four younger siblings fled on foot, leaving the rest of their family behind.

They walked for days through harsh terrain to South Sudan’s capital, Juba. After a few days of rest, they continued on, crossing Kenya’s border. The United Nations Refugee Agency then resettled them in Kakuma.

“I believe hunger can end, but only through hard work,” Waad says. “If you just sit and depend on others, hunger will never end.”

Helping out ‘neighbours’

Kansas farmer Keesling has also met with Kakuma refugees like Waad. He became involved in food aid 25 years ago, after missions to the Middle East and Cuba for the Kansas wheat industry.

“Africa has always been a love for me – trying to understand the continent and how African farmers can succeed,” says Keesling, who has since travelled to every African country and visited WFP projects.

Keesling has seen hunger’s devastating impact firsthand, but also success stories. Like one woman in Ethiopia, he says, who overcame sexual violence and went on to open a WFP-supported orphanage.

He recalls how his grandfather overcame poverty nearly a century ago – by winning a bare-knuckle fight. With the prize money, Keesling's grandfather paid off the family’s debts so they could start anew.

“Farmers in the Midwest always have the heart of helping their neighbour out – and we view ‘neighbour’ as someone who is not restricted by miles,” Keesling says. “I’ve seen from my travels that when you give food, you give hope. And when you have hope, you find ways to fix things.”

With thanks to WFP USA for contributing to this story.

WFP’s operations in Kakuma are made possible through funding from the European Union Humanitarian Aid (ECHO), Germany, Japan, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the Republic of Korea, the United Kingdom and the United States.