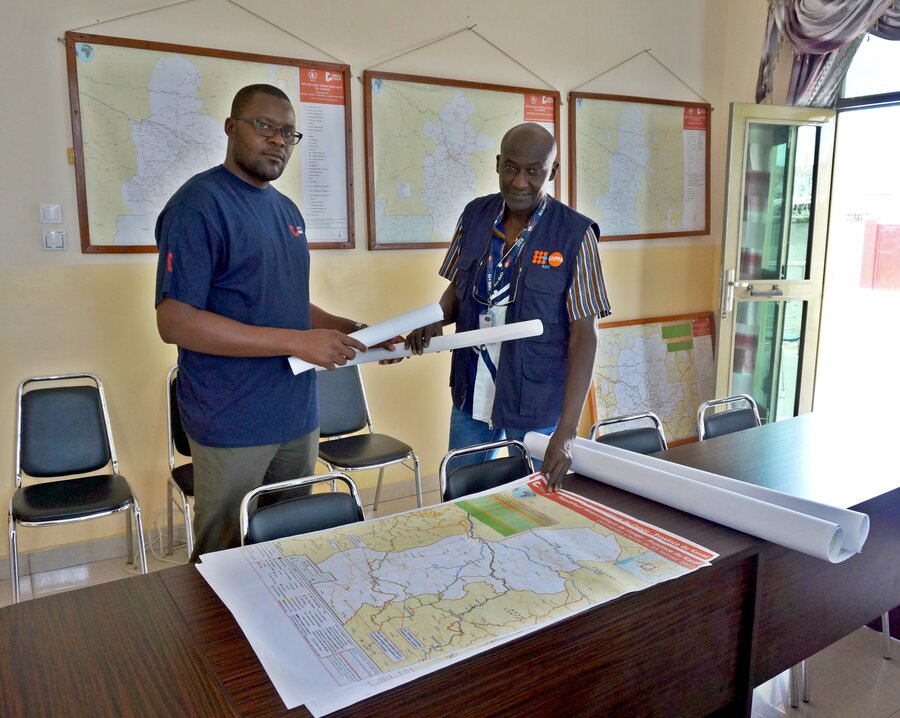

Maps: The heart of any logistics response

It's early morning and the office is still quiet. My three screens are glaring, one with attribute tables, one with the visuals and one to help me track the requests coming in.

It won't be long before the phone starts ringing off the hook. Many of those calls will be partners asking for maps. Good thing I have already turned on the plotter.

"Good maps will allow aid to reach beneficiaries fast; bad maps can leave you stranded for days."

From logistics planning maps to access constraints maps, I receive dozens of requests every day. I do my best to respond because I know the stakes are high.

Maps are at the heart of any logistics response, and can make the difference between a successful operation and a setback. Good maps will allow aid to reach beneficiaries fast; bad maps can leave you stranded for days. This is where I come in.

Data collection for maps requires method and precision. Everyone involved in a crisis response should know how to properly use GPS to collect information that is accurate. I have trained many staff members and partners on how to do this. I know I can count on them for information, and they can rely on me for transforming that same information into useful maps.

Last year, over 8 million people were in need of humanitarian assistance in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The Kasai crisis made matters worse, with the current figure now standing at 13 million. Then in May of this year, the western Equateur Province saw its ninth outbreak of the Ebola virus in the last four decades, causing over 25 deaths in less than a month. In this environment, humanitarians can't afford delays; assistance has to be provided as quickly as possible.

But the DRC is a vast country and the physical constraints are numerous. Waterways, roads and airports aren't always mapped accurately, and sometimes, aren't even mapped at all.

"Technology is facilitating my role as a humanitarian, one map at a time."

OpenStreetMap has been key in changing this. By allowing individuals to digitize existing satellite imagery, the collaborative mapping platform is slowly improving baseline data for maps, one topographical element at a time.

This wouldn't be the first time that OpenStreetMap is being used in a crisis context. West Africa was rocked by an outbreak of the Ebola virus in 2014 that infected 28,600 men, women and children and killed 11,300. WFP provided emergency food and helped transport partners' supplies and staff throughout the region. Through the OpenStreetMap, the humanitarian team created tasks for individuals to map infrastructure and before long, aid workers were able to deliver.

Not very long ago, I would draw blank stares when I would say that I was a GIS officer. Spatial and geographic data were once obscure terms but with the advent of smartphones, people have become more sensitive and attuned to mapping. Technology is facilitating my role as a humanitarian, one map at a time.

Ladislas Kabeya is a GIS Officer for the Logistics Cluster based in Kinshasa, DRC. Last year, the WFP-led Logistics Cluster supported 185 organisations in the DRC, including with the production of customized maps.