Women’s day: Mangrove oysters mean food security for a family in Ecuador

“Without the mangroves there is no life for us,” says Rosa of the swamp area that serves as a protective ecosystem for the community of Punta de Miguel near Ecuador’s border with Colombia.

Here, in the Mira-Mataje Mangrove Reserve, she goes out picking mangrove oysters – these provide a source of nutrition for her family, and she can also sell them on to earn an income.

The area is vulnerable to both the El Niño and La Niña phenomena – literally the boy and girl, they refer to patterns of sea surface temperature in rises in the tropical eastern Pacific and decreases in the central tropical Pacific respectively.

Thankfully, the thicket of roots created by the mangrove trees provides a natural barrier against the slings and arrows of extreme weather, allowing hundreds of families to continue a tradition of artisanal fishing.

“The mangroves mean a lot to me because this is where we grew up, it is where our food is produced,” says Rosa, a migrant from Colombia. “It is our life.”

Rosa is a conchera, and leads her husband, José, and their son, in collecting mangrove oysters. It’s no easy task – they must wake up at the crack of dawn, often skipping breakfast to leave the house by 5a.m.

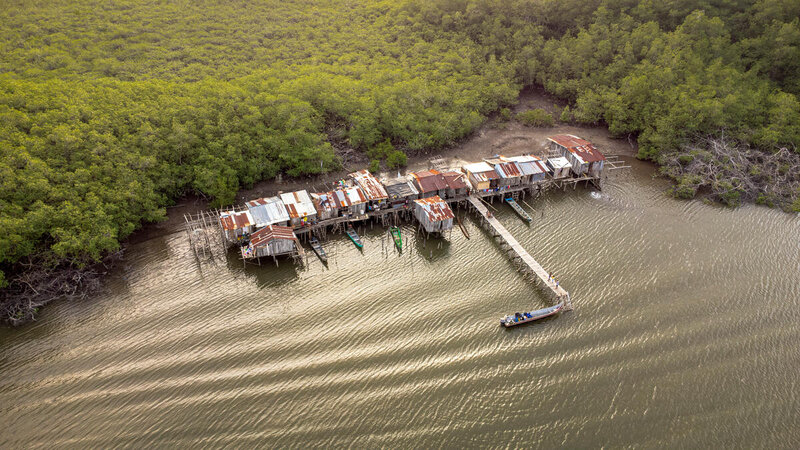

They then cross the mangrove swamp by boat until they reach areas where they can ‘shell’. Rosa’s boat is emblazoned with the message ‘Rosita (her nickname) thanks God’.

Once in place, she and José light a wick – the smoke helps to keep insects away – and wade waist-deep through the mud, feeling for shells in crevices. Insect bites are not the only concern – every day Rosa and her companions risk getting trapped among the roots, being stung by toadfish or bitten by the snakes that hide within the groves.

The number of shells they collect depends on the tide and the time they spend in the mangroves – usually five to six hours a day. After filling their baskets one shell at the time, they clean their catch and and return to the port to wait for traders – 300 shells can fetch US$30.

Mangroves in danger

Despite their importance as ecosystems and for the survival of local communities, in the past four decades thousands of hectares of mangrove have been lost to human actions, such as deforestation, or to climate-related events.

Rosa says El Niño has brought intense rains and high tides. Sometimes for weeks at a time, she cannot collect shells because the water covers the mangrove roots and mud. And no shells means no income.

To protect the mangroves, Rosa participates in a reforestation project led by the Government of Ecuador with the support of the World Food Programme (WFP).

Just as collecting shells, reforestation is hard work. After sowing the seeds, Rosa and other members of her Afrodescendant community must clear the weeds to protect the small mangrove trees.

“If the mangrove disappeared, it would be the end of our lives because we live off them,” says Rosa. “Without mangroves, there is no life for us.”

The climate change adaptation project – covering the reforestation of 400 hectares of land and the conservation of 15,000 hectares of mangroves – involves 66 communities, of whom 38 are of African descent while 28 are from the Awá indigenous community. Both groups live along the border of Colombia and Ecuador, specifically in the Mira-Mataje and Guáitara-Carchi binational watersheds.

The watersheds have been severely degraded due to human interventions such as waste disposal and deforestation, and climate variability such as high tides, El Niño and La Niña, which affect the community livelihoods, life and food security. The Binational Project, financed by the Adaptation Fund, seeks to implement innovative measures for adaptation to climate change, with an emphasis on food security.