Wars, airdrops and pythons: reflections from retiring WFP Chief of TV

For more than two decades, the World Food Programme’s (WFP) Head of Television Communications, Jonathan Dumont, has documented humanitarian crises in some of the most remote and dangerous parts of the world - helping to catalyse global action and support for our hunger-fighting work. Dumont’s coverage has shone a spotlight on dire needs after earthquakes in Iran, a tsunami in Sri Lanka and floods in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. He’s perched next to gaping hatches of cargo planes dropping food for starving people over South Sudan, interviewed families fleeing armed groups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Haiti, and witnessed famished children sift through Gaza’s rubble in a desperate search for sustenance. Also memorable: some uncomfortably close encounters with snakes. On the eve of retiring from WFP, Dumont describes the perils - and paybacks - of capturing the faces of hunger.

How does it feel to be leaving WFP after so many years?

I’m grateful for the experiences that I’ve had, covering stories on the frontlines of hunger - from Pyongyang to Port-au-Prince, Gaza to Goma, Kabul to Kyiv. I’ve been to corners of the world that are out of reach for most journalists. I feel like I’ve been able to contribute, and do some good, and focus attention on food insecurity - and the impact of WFP’s life-saving work. But, most importantly, I’ve been privileged to give a voice to the hidden hungry - vulnerable families who count on us to share their stories.

You joined WFP in 2003 - what were those early days like?

It wasn’t all emergencies. When I first started, for example, an advertising agency produced a corporate video for WFP with a Sean Connery-like voice. And I said: "Why don’t we just get Sean Connery?" So I tracked him down and convinced him to be involved. After the 2008 financial crisis, and the rescue plans (for banks), I thought: "What about the human rescue plan - how much would it cost to feed hungry people?" So I contacted Sean Penn - and he agreed to be part of that WFP public service announcement to support them. I also produced a graphic novel about WFP staff working in places like Iraq, South Sudan and the Sahel.

How did WFP’s coverage of hunger change over time?

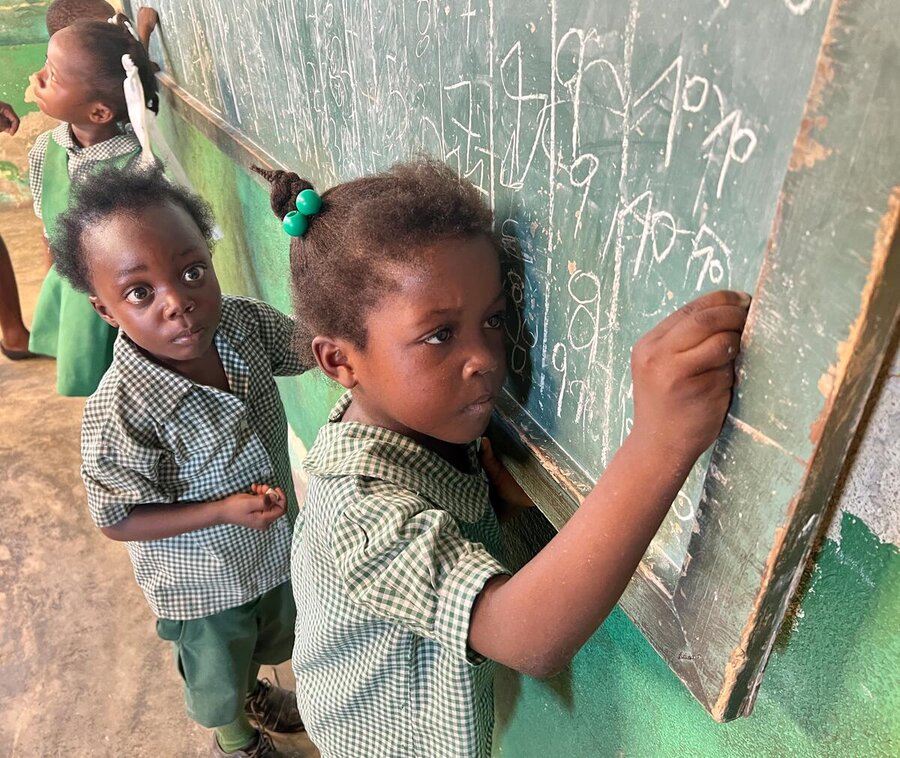

As we started to see more and more big, mostly conflict-driven emergencies, it made sense to focus on these important stories. Since journalists often can’t get to many of these places, we decided to focus on positioning WFP in the media as an expert and reliable source of content and information about humanitarian crises - and ensuring what we share is factual and verifiable.That’s helped us earn the trust of news organizations, donors and inevitably the public - who have donated millions and millions of dollars to help us fight hunger. It all comes down to telling the personal stories of people in these places.

You’ve had so many experiences - what are some takeaways?

The scale and intensity of the violence in Gaza has been one of the most unforgettable experiences I’ve had covering conflicts. The destruction in this narrow strip of land, filled with people trapped and struggling to survive, has been staggering.

"The scale and intensity of the violence in Gaza has been one of the most unforgettable experiences I’ve had covering conflicts."

Our colleagues there are living their work. They spend their days trying to get food to those who need it most - and then go home to face the very same challenges: trying to figure out how to find food, water and fuel for their own families. For me, they are the faces of WFP. They are my heroes.

How do you cover dangerous places?

We can’t go where we haven’t convinced those in power to allow us to go. And that happens thanks to our incredible colleagues who specialize in access - so we can reach the most vulnerable people in need safely, independently and impartially. They talk to the militias, the criminal gangs, the military leaders and convince them to let us in to places like City Soleil [a gang-controlled neighbourhood in Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince] - where arguably some of the most dangerous people on the planet have agreed to let us bring in food for civilians. I’ve also reached remote villages in Afghanistan and DRC. I’m privileged because I can also leave these places - but the people living there are often trapped. So, I feel I have a responsibility to tell their stories.

"I sometimes slept on floors. I've found pythons living in pits serving as latrines."

Early on, I sometimes slept on floors. I've found pythons living in pits serving as latrines [in South Sudan] - I hate snakes - and lots of other slithering, flying, crawling things. A lot of progress has been made since to improve staff well being. On the other hand, 383 humanitarians were killed in 2024 - that’s an all-time record.

You’ve also seen WFP’s impact up close…

One thing I still remember is being in the desert in eastern Chad. You see these trucks come over the horizon with vital WFP food for people who fled fighting in Sudan. The amount of logistics and teamwork - and the skill involved in negotiating to get there, working together to deliver to some of the hardest-to-reach places - that’s something we should be proud of. It’s what we do - and we do a really good job. That’s one of the reasons why WFP was awarded the [2020] Nobel Peace Prize.

What’s left you energized?

Haiti. It has some of the strongest, most compelling, vibrant, determined people I’ve ever met. Their country has gone through so much - from its colonial legacy and debt, to political and economic collapse, to natural disasters and extreme violence by armed groups. And yet Haitians are in the hills, digging and planting - even though the next storm could wash everything away. Their strength and determination leaves me in awe.

What’s next for you?

I want to make films and tell stories - those that aren’t about reality for a change. But I’m leaving at a moment when it’s a hard time to be a humanitarian: it's dangerous, logistically challenging and funding is in short supply. That’s when empathy and compassion come in. Fundamentally, people are empathetic - they want to help. Empathy makes us stronger. It empowers the global community to act, to help solve problems. The world still needs the UN - and WFP - now, more than ever. I wouldn’t have stayed 22 years if I didn’t think the job was worth it.