Aleppo, Syria: ‘Each day that comes is worse than the one before’

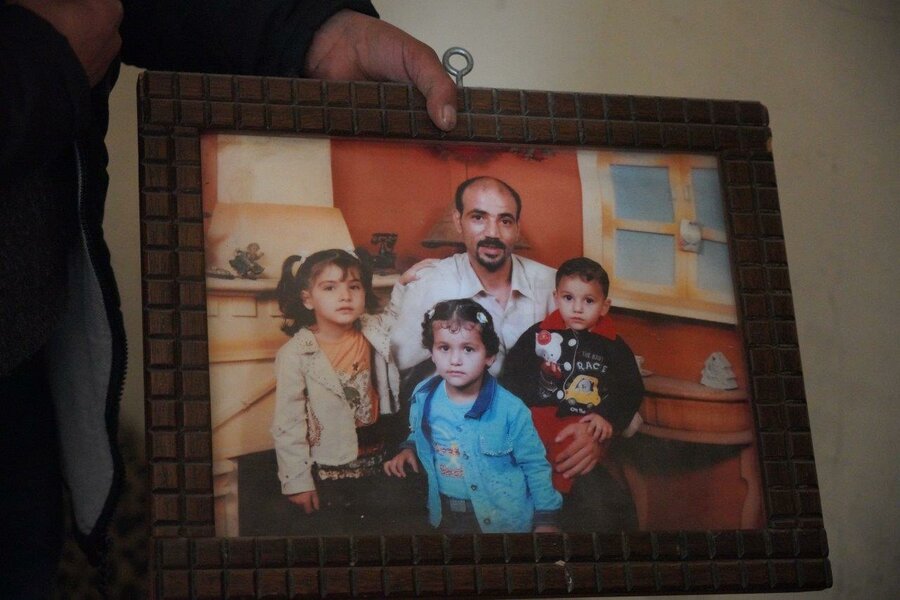

When visiting families in Aleppo, you always need light to find the way — up several flights of stairs in the dark and the cold, wondering what we’ll see when a family opens a door. An empty refrigerator, no electricity and some old photos on the wall. This is what’s left after a decade of conflict in Syria.

Abo Hashim, who is in his forties, grew up in a city filled with beauty. With bustling markets bursting with spices, food, travellers from around the world and a growing economy, he had everything he needed.

Syria: ‘If it wasn’t for WFP’s airdrops, we would have died’

Several decades later, he’s a father of six children, unemployed and facing the worst economic crisis Syria has ever seen. After living through years of conflict and displacement, soaring food prices have put even basic foods beyond reach. When he talks about struggling to feed his family, he says “the pain that I live with cannot be described”.

“Each day that comes is, unfortunately, worse than the one before,” he adds. “The days are becoming harsher. We used to manage our living needs with simple solutions, but now you can’t.”

In Abo Hashim’s life, almost everything has changed. When he was a child, his father used to buy an entire cart of watermelons for his family. He can remember having a refrigerator full of cheese and cupboards full of olive oil. Food was affordable and in abundance in Syria’s economic capital.

Photo: WFP/Hussam Al Saleh

“This summer I think I bought only one or two watermelons, that’s it. We used to buy labneh [cheese] in tens of kilos. Now we buy it in grams. When I was child, if I consumed a kilogram, no one would notice or be upset. I have not bought a bottle of olive oil for three years. We used to think of the good life and leisure but now we only think about where we are going to get our next meal.”

He recalls buying small amounts of gold when he was a teenager, to celebrate Eid. As an adult, he sold his wife’s wedding ring so his family could meet their basic needs.

Families have paid an unimaginable price for a decade of conflict. Today, a record 12.4 million people — that's 60 percent of the population — are food-insecure, more than ever recorded in Syria.

Behind closed doors, Syrians shiver in freezing apartments — electricity is scarce. They wait for hours to buy bread, fuel and life necessities. Like the rest of the world, Syrians worry about COVID-19. But on top of that, they worry about where their next meal will come from.

With prices rising every month, the value of Syria’s currency is falling and the peaceful life that millions dreamed of slips further away.

A beautiful three-month-old baby girl sits on Abo Hashim’s knee. She is passed back and forth between her parents while they speak.

“When my first child Raba’a was born, the living conditions were still excellent,” says Abo Hashim. “I rented a house in Lebanon and brought my wife to Lebanon to give birth in a private hospital.”

In contrast, Shaghaf, who has five siblings, was born in Aleppo and her parents depend on humanitarian assistance to survive.

I had to take two of my children out of school because we need income to survive

Each month they receive an electronic voucher from the World Food Programme (WFP) to buy the food they need. This was provided to Abo Hashim’s wife Noor when she was pregnant, so she could improve her nutrition; with support from the United Nations Population Fund, she can buy hygiene items to help her family stay safe during the COVID-19 pandemic. She says she chose to buy diapers for her baby, as well as cheese, olives and eggs — items they couldn’t afford otherwise.

But economic pressures — and heartbreak — are growing. Children across Syria are now starting to pay the price for the country’s economic deterioration.

“I had to take two of my children out of school because we need income to survive,” says Abo Hashim. “I need to feed the family, and this is the most important priority, not anything else.”

The day we meet is his 15-year-old son’s third day of work as a carpenter. His daughter was a good student but the family couldn’t afford the notebooks and pens. She now stays at home and helps to care for her younger siblings.

“What will the coming days bring with it for my children? From what we have seen it is going to be worse, unfortunately. My wife visits her mother and brings back some food so she could feed the children. It seems that the coming days will bring my children nothing but misery,” he says.

“My son is ten years old. I don’t allow him to spend time in the street — not because it is dangerous, but because I am afraid that he might see something he likes and ask for it and I can’t buy it for him.”

Window on Syria: A WFP photographer looks back at a decade of conflict

“Previously, you used to need 1,000 or 2,000 Syrian pounds [around US$1.50] for daily living. Now you need 20,000 SYP, so you could say the difficulties have multiplied 10 or 15 times.

“You can’t describe the pain you feel when your child is hungry, when they are feeling cold, when you can’t fulfil their basic living needs. Nothing can describe this pain.”

Humanitarian assistance has never been so important, and the needs across Syria have never been greater.

Each month WFP provides lifesaving food to 4.8 million Syrians. Over 75,000 pregnant and nursing mothers like Noor receive an electronic food voucher to buy healthy food and boost their nutrition during a critical time of their lives. This is the best chance for babies like Shaghaf to have a healthy start to life, and to have hope that the next decade in Syria will be better than the last.